The Relocation of Japanese American Students to Wayne University during World War II

The following is a guest post by Devin Erlandson, recipient of the Ronald Raven Annual Award and the Summer 2014 intern for the Wayne State University Archives.

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 which excluded all people of Japanese ancestry from living on the Pacific coast. Of the 127,000 Japanese Americans living on the West Coast, 112,000 were sent to internment camps. 2,000 Nisei (second-generation Japanese Americans with American citizenship) were uprooted from colleges and universities—their academic future was suddenly very uncertain.

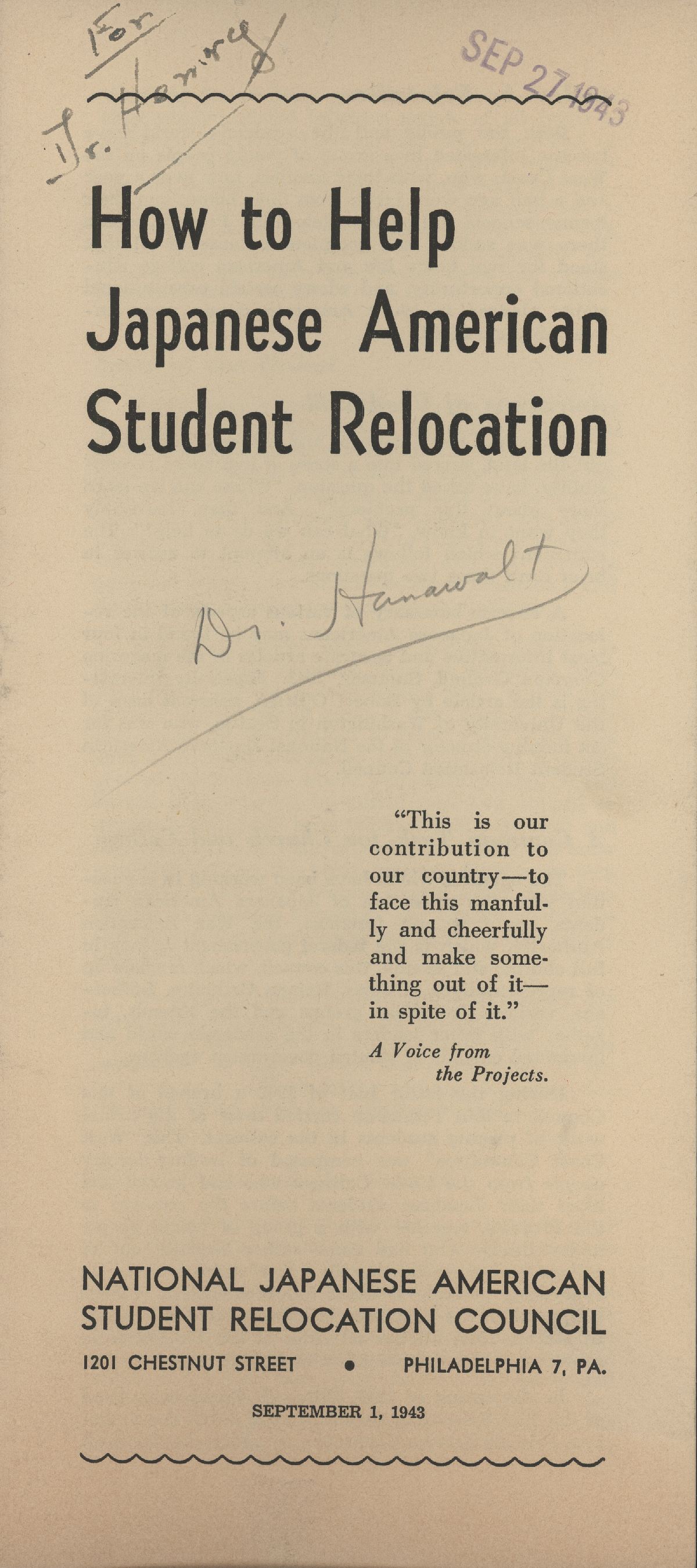

The National Japanese American Student Relocation Council, sponsored by the American Friends Service Committee, worked to relocate and resettle Nisei students at Midwestern and East Coast colleges and universities. One such institution was Wayne University. By the time the NJASRC closed its doors in 1946, it had helped 4,000 students to continue their higher education at over 600 institutions, and evidence of Wayne's efforts in this project can be found in the Wayne University Admissions Office and Acting Registrar Records, 1940-1947.

Wayne University was cleared by the War Department and the Navy Department for the purposes of student relocation in 1942. Working with the War Relocation Authority, Wayne and the NJASRC began the process of accepting and relocating students to Detroit. The NJASRC handled all correspondence, examination of student records, alien questionnaires to be filled out by all students, and the selection and placement of Japanese American students.

In the summer of 1943, before the university began its relocation efforts, five Japanese American students were already attending Wayne University. Wayne started to formally accept relocated students that summer, and by the fall semester of 1943, thirteen relocated students were enrolled. Eleven of those thirteen students completed their first semester. In the second semester, thirty-five relocated students were enrolled at Wayne—twenty-five of whom were new students. John R. Moseley wrote on May 26, 1944: “There have come to this office about 100 inquiries by letter. In addition to these written inquiries, a number of students already located in Detroit have visited our office and have been interviewed by one of the counselors.” He continued: “...as far as the Japanese American students are concerned, at the present time there is no intention of limiting the number of such students who come to this University, as long as they fulfill our scholastic requirements.”

The largest hurdle the Wayne University Admissions Office faced in accepting Nisei students was the Provost Marshal General’s Office. The Provost Marshal General initially restricted any Nisei students from enrolling in an institution “engaged in research, developmental or training activities for the Army or Navy” arguing that such institutions would be “considered as a facility important to the war effort, and the interested procurement agency must request consent for the admittance or employment of persons of Japanese ancestry” (January 26, 1944, United States Army correspondence). The Admissions Office strongly protested this stipulation, and opposed requiring Nisei students to fill out alien questionnaires. On February 12, 1944, the NJASRC wrote to Moseley to express its relief that “until further notice, students of Japanese ancestry desirous of attending Wayne University will not require clearance by [the Provost Marshal General’s] office. We feel sure that this is due to your strenuous protest.”

Wayne University was quite proud of the performance of the students. A March 8, 1944 letter from Wayne University President David D. Henry to Leslie L. Hanawalt, Acting Registrar and Director of Admissions, describes the academic accomplishments of the Nisei students as “a remarkable performance.” In the same letter Dr. Henry describes them as “among the most considerate and reasonable people that we have dealt with in the Admissions Office.” John R. Moseley of the Admissions Office wrote: “In talking with various students of the Japanese American group, I have been well pleased with the attitude which they are taking towards their work here” (March 6, 1944 correspondence). On May 1944, Moseley wrote to Harry Weiss of the War Relocation Center about community acceptance:

It has been a pleasure to me personally to see our Japanese American students taking an active part in the bull sessions which occur daily about the halls, to see them troupe across the street to the corner drugstore to have a Coke, and to find them sitting on the benches around the courtyard discussing with animation some topic of interest with other students. I have heard of no case whatsoever in which there has been any tendency on the part of our regular students to consider our friends from California any other than fellow students.

Despite the fact that these Nisei students and other Japanese Americans, including their parents, friends, and neighbors, were forcibly removed from their homes and placed in internment camps, many of them simply wanted to return to college. With the support of the National Japanese American Student Relocation Council, and educational institutions like Wayne University, this was a possibility. At Wayne, Nisei students were welcomed, treated like any other student from Detroit, and thrived in their academic environments.

The correspondence between the Admissions Office, the NJASRC, and the War Relocation Authority highlights an important aspect of World War II history. It also tells a story of diversity at Wayne University: the administration wanted Japanese American students to come to Detroit, they protested against the extra red tape the Provost Marshal General wanted to impose, and they boasted to other colleges that Nisei students were remarkable. For anyone wishing to research the administrative side of the Japanese American student experience, these letters prove a valuable resource.

Devin Erlandson is an MLIS candidate at the Wayne State University School of Library and Information Science.

- Public Relations Team's blog

- Login to post comments

- Printer-friendly version

Reddit

Reddit Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn