Subject Focus: Merrill-Palmer Summer Camp

With the school year now upon us, the Reuther Library presents a look back at summers past as recorded in the Merrill-Palmer collections. As Edna Noble White, first director of the Merrill-Palmer Institute, once said, "The children of a nation are its greatest potential asset." This belief was reflected in the Institute's main role, which was the understanding and interpretation of the individual from birth to adulthood.  With the success of the nursery school, established at the Institute in 1922, their initial focus on early childhood quickly expanded to include the study of children through to adolescence. Just seven years after its inception, weekly recreation groups for children ages five and up were added. The need for prolonged observation led a year later, in 1930, to the formation of the first sponsored summer camp, called The Merrill-Palmer Farm Camp (known later as simply the Merrill-Palmer Camp). This six-week camp afforded advanced opportunities to study the social and cognitive growth of pre-adolescent children, aged five to twelve, in a 24-hour recreational setting. Adhering to the mutually beneficial philosophy of the nursery school, the camp also gave area school-age children the "unquestioned advantage" of supplementing their regular school year learning with outdoor education in the summer months. While based on the same premise as a classic summer camp, it nevertheless was unusual for its time. The fact that it was used as an outdoor lab by leaders in the field of child development, its staff and camper populations were co-ed, and campers actively participated in camp governance seems innovative even by today's standards.

With the success of the nursery school, established at the Institute in 1922, their initial focus on early childhood quickly expanded to include the study of children through to adolescence. Just seven years after its inception, weekly recreation groups for children ages five and up were added. The need for prolonged observation led a year later, in 1930, to the formation of the first sponsored summer camp, called The Merrill-Palmer Farm Camp (known later as simply the Merrill-Palmer Camp). This six-week camp afforded advanced opportunities to study the social and cognitive growth of pre-adolescent children, aged five to twelve, in a 24-hour recreational setting. Adhering to the mutually beneficial philosophy of the nursery school, the camp also gave area school-age children the "unquestioned advantage" of supplementing their regular school year learning with outdoor education in the summer months. While based on the same premise as a classic summer camp, it nevertheless was unusual for its time. The fact that it was used as an outdoor lab by leaders in the field of child development, its staff and camper populations were co-ed, and campers actively participated in camp governance seems innovative even by today's standards.

The Farm Camp drew its male and female counselors mostly from current Merrill-Palmer staff and students in the areas of education, psychology, home economics, sociology, group work, medicine, child development, anthropology, and physical growth. In the camp's first year, Elise Hatt Campbell, a Merrill-Palmer staff member, served as head counselor. She recorded her experiences and observations in a logbook (Merrill-Palmer Institute Records, Box 80, Folder 12), providing unique insight through words and photographs. The staff structure remained essentially the same throughout the years, allowing counselors to work as either group leaders or field leaders in the areas of waterfront, arts and crafts, and nature study. A camp brochure from 1951 indicates ten or more graduate students and five adults led fifty campers that year – approximately a 1:3 counselor to camper ratio. Often the Institute's director served on staff, and Detroit Public School teachers and area child psychologists served as camp directors.

The Farm Camp drew its male and female counselors mostly from current Merrill-Palmer staff and students in the areas of education, psychology, home economics, sociology, group work, medicine, child development, anthropology, and physical growth. In the camp's first year, Elise Hatt Campbell, a Merrill-Palmer staff member, served as head counselor. She recorded her experiences and observations in a logbook (Merrill-Palmer Institute Records, Box 80, Folder 12), providing unique insight through words and photographs. The staff structure remained essentially the same throughout the years, allowing counselors to work as either group leaders or field leaders in the areas of waterfront, arts and crafts, and nature study. A camp brochure from 1951 indicates ten or more graduate students and five adults led fifty campers that year – approximately a 1:3 counselor to camper ratio. Often the Institute's director served on staff, and Detroit Public School teachers and area child psychologists served as camp directors.

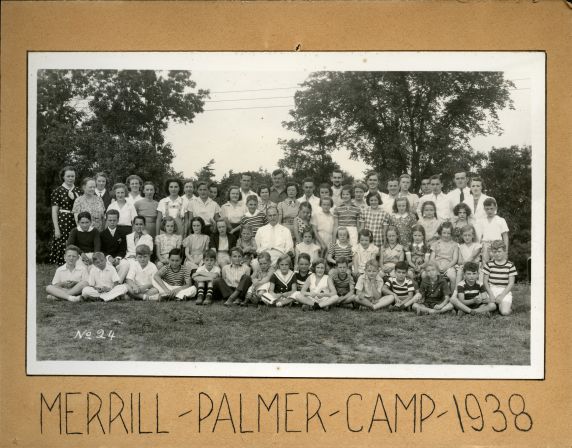

Male and female campers were accepted, in as equal numbers as possible, with preference given to Merrill-Palmer children. The intent was to include children, as much as possible, from different socio-economic backgrounds, races, and ethnicities. Counseling Services recommended camp as an extension of treatment for a handful of children and partial scholarships were available for those that could not afford the full cost. Edna Noble White's own son attended the first year alongside children of physicians, gardeners, manufacturers, and merchants. There were 14 boys and 12 girls in the first camp season, growing to 75 total children attending by 1955. Parents provided information about their child and their expectations prior to camp, and camp counselors evaluated them throughout their stay, providing reports on each individual child at the conclusion of camp. These reports detailed a child's physical health (e.g. eating and sleep habits), responsibilities for self and group, social adjustments, and achievements (e.g. riding, waterfront, nature lore, camp craft, and music). Data collected that first year measured a child's body weight, personality traits, intellect, and social behavior. As the years progressed, analysis of this data along with other types of data, such as activity preferences, would inform research projects and articles. Studies such as Marian Breckenridge's “Food Attitudes in a Group of 5 to 12 Year Old Children Attending Camp,” for example, were published.

Male and female campers were accepted, in as equal numbers as possible, with preference given to Merrill-Palmer children. The intent was to include children, as much as possible, from different socio-economic backgrounds, races, and ethnicities. Counseling Services recommended camp as an extension of treatment for a handful of children and partial scholarships were available for those that could not afford the full cost. Edna Noble White's own son attended the first year alongside children of physicians, gardeners, manufacturers, and merchants. There were 14 boys and 12 girls in the first camp season, growing to 75 total children attending by 1955. Parents provided information about their child and their expectations prior to camp, and camp counselors evaluated them throughout their stay, providing reports on each individual child at the conclusion of camp. These reports detailed a child's physical health (e.g. eating and sleep habits), responsibilities for self and group, social adjustments, and achievements (e.g. riding, waterfront, nature lore, camp craft, and music). Data collected that first year measured a child's body weight, personality traits, intellect, and social behavior. As the years progressed, analysis of this data along with other types of data, such as activity preferences, would inform research projects and articles. Studies such as Marian Breckenridge's “Food Attitudes in a Group of 5 to 12 Year Old Children Attending Camp,” for example, were published.

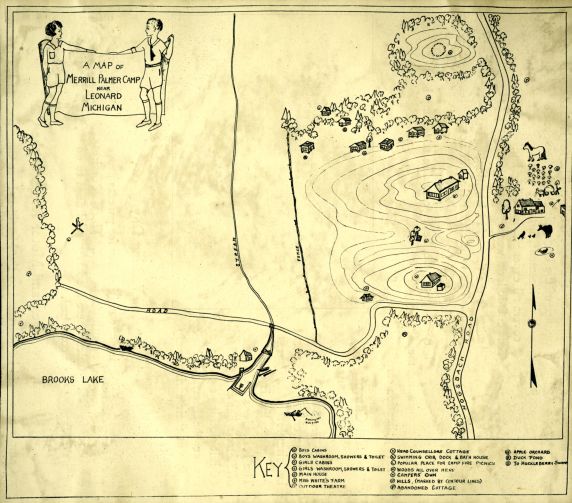

Located forty miles north of Detroit on Brooks Lake, the American Camping Association accredited camp straddled the border of Oakland and Lapeer counties. It encompassed over 200 acres of woods, hills, and farmland (in the early years, Edna Noble White's adjacent farm was used extensively). Facilities included one-room cabins with beds, modern bath buildings, and electricity. Cabins accommodated four to six children and two adults - a group organization similar to that of a family unit. The health and safety of the campers was addressed through daily meals prepared by a dietician and required rest times, which included an afternoon nap, thirty minutes of quiet time before lunch and dinner, and a long night's sleep. An infirmary was maintained on the grounds, with the nearest hospital only ten minutes away. Family visits were allowed on Sundays. The cost in 1951 was $240, or $40 per week.

Located forty miles north of Detroit on Brooks Lake, the American Camping Association accredited camp straddled the border of Oakland and Lapeer counties. It encompassed over 200 acres of woods, hills, and farmland (in the early years, Edna Noble White's adjacent farm was used extensively). Facilities included one-room cabins with beds, modern bath buildings, and electricity. Cabins accommodated four to six children and two adults - a group organization similar to that of a family unit. The health and safety of the campers was addressed through daily meals prepared by a dietician and required rest times, which included an afternoon nap, thirty minutes of quiet time before lunch and dinner, and a long night's sleep. An infirmary was maintained on the grounds, with the nearest hospital only ten minutes away. Family visits were allowed on Sundays. The cost in 1951 was $240, or $40 per week.

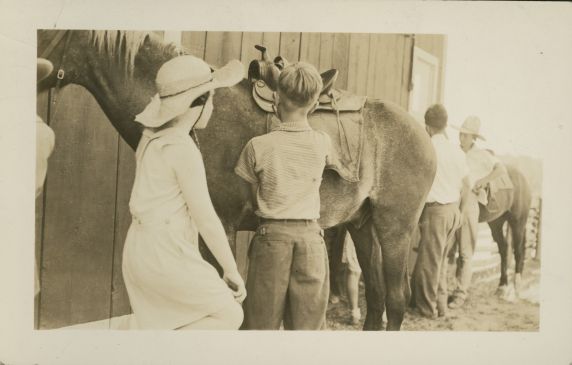

The camp program offered a variety of pursuits: waterfront activities (swimming, boating, and fishing); arts & crafts; nature education; overnight hiking trips and outdoor living skills; music, drama, and dance; free play and games (tennis, badminton, archery, horseback riding); reading; and special trips. In 1940, a farm life component was added that introduced campers to the care of farm animals and the growing of crops. An important component of the program were the twice daily meetings among counselors and their campers, held in order to ascertain individual interests among the children and get their input in daily planning. Progress toward individual goals was charted and became part of the assessment undertaken by the counselors as they kept logs recording the planning, execution, and results of these meetings. This democratic approach to programming led to new activities and events introduced each year, within the framework outlined above. The result was that no two years were exactly the same. A typical daily schedule (7:30 a.m. – 8:30 p.m.) included: a medical exam; meals and snacks; water play and swimming; quiet times and nap; general and evening activities, including movies once a week; and general assembly.

The camp program offered a variety of pursuits: waterfront activities (swimming, boating, and fishing); arts & crafts; nature education; overnight hiking trips and outdoor living skills; music, drama, and dance; free play and games (tennis, badminton, archery, horseback riding); reading; and special trips. In 1940, a farm life component was added that introduced campers to the care of farm animals and the growing of crops. An important component of the program were the twice daily meetings among counselors and their campers, held in order to ascertain individual interests among the children and get their input in daily planning. Progress toward individual goals was charted and became part of the assessment undertaken by the counselors as they kept logs recording the planning, execution, and results of these meetings. This democratic approach to programming led to new activities and events introduced each year, within the framework outlined above. The result was that no two years were exactly the same. A typical daily schedule (7:30 a.m. – 8:30 p.m.) included: a medical exam; meals and snacks; water play and swimming; quiet times and nap; general and evening activities, including movies once a week; and general assembly.

Due to the overwhelmingly positive response from parents, the Institute added a family camp in 1949, which took place during the two weeks immediately following the six-week children's camp. For $25 a week per person, twelve families could set up in their own cabin. Camp staff remained, and along with the participating families and within the confines of the facilities, established the program. Except in 1943, camp was held every summer, but by 1959 expenses were proving difficult in keeping either camp operational. In 1961 the Board of Trustees passed a formal resolution to sell the summer camp property. Despite push back from some faculty members, by 1964 the summer camp program had ended. Further information on the camps can be found primarily in the Merrill-Palmer Institute: Dr. Pauline Park Wilson Knapp Records and the Merrill-Palmer Institute Records. To further explore photographic materials, please contact a member of our Audiovisual Department to make an appointment.

Due to the overwhelmingly positive response from parents, the Institute added a family camp in 1949, which took place during the two weeks immediately following the six-week children's camp. For $25 a week per person, twelve families could set up in their own cabin. Camp staff remained, and along with the participating families and within the confines of the facilities, established the program. Except in 1943, camp was held every summer, but by 1959 expenses were proving difficult in keeping either camp operational. In 1961 the Board of Trustees passed a formal resolution to sell the summer camp property. Despite push back from some faculty members, by 1964 the summer camp program had ended. Further information on the camps can be found primarily in the Merrill-Palmer Institute: Dr. Pauline Park Wilson Knapp Records and the Merrill-Palmer Institute Records. To further explore photographic materials, please contact a member of our Audiovisual Department to make an appointment.

Deborah Rice is an Audiovisual Archivist at the Walter P. Reuther Library

- drice's blog

- Login to post comments

- Printer-friendly version

Reddit

Reddit Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn