The Southern Airways strike of 1960: ALPA’s epic battle over fair wages for pilots

By the late 1950s, it was becoming increasingly clear that the Air Line Pilots Association (ALPA) would have to strike against Southern Airways (SOU). The main issue was wages. The union maintained that all of their aviators should receive the same salary regardless of the size of the airline, but SOU, a smaller, regional carrier, claimed they could only afford to pay a lower rate. ALPA knew this was a battle they had to take on, though it would not be easy. Frank Hulse, the founder and president of SOU, was staunchly anti-union, and had recently succeeded in breaking up the mechanic’s union at Southern Airways. ALPA was the last union standing at SOU.

In the early part of 1959, contract negotiations began between ALPA and SOU, and a walkout seemed inevitable. There were stories circulating that Hulse actually wanted a strike. Although SOU was a minor operation, ALPA president Clarence Sayen was concerned that if Southern Airways was able to break the union, other airlines would certainly attempt to do the same.

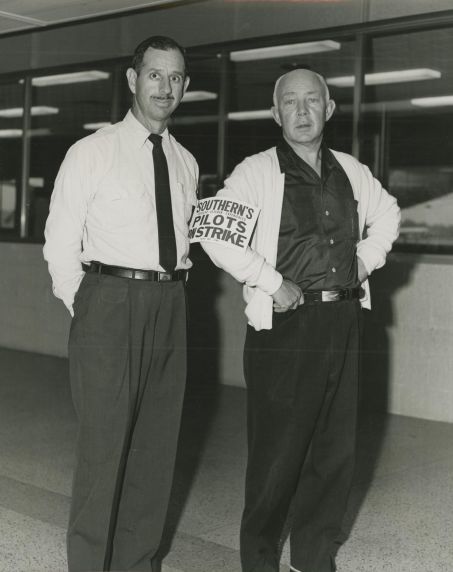

After over a year of negotiations, the strike began on June 5th, 1960. During the early days of the conflict, spirits were high at the strikers’ home base, the Memphis Holiday Inn, as few felt it would last. ALPA had succeeded in convincing the newly laid-off aviators of Southeast Airlines—pilots Hulse was expecting would replace the strikers—not to cross the picket line. ALPA had won the first battle.

After over a year of negotiations, the strike began on June 5th, 1960. During the early days of the conflict, spirits were high at the strikers’ home base, the Memphis Holiday Inn, as few felt it would last. ALPA had succeeded in convincing the newly laid-off aviators of Southeast Airlines—pilots Hulse was expecting would replace the strikers—not to cross the picket line. ALPA had won the first battle.

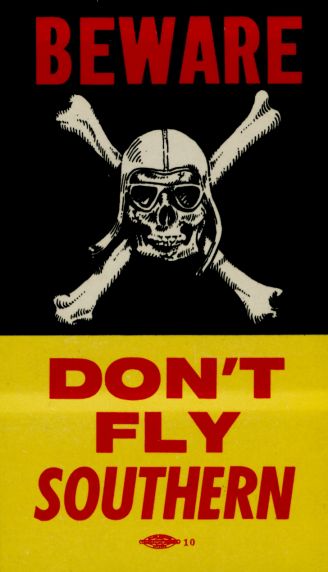

Eventually, Hulse did find substitutes, as pilot jobs were scarce at the time, despite the fact that the wage he was offering was insultingly low. ALPA members created their own files on the strikebreakers, as the FAA wasn’t interested in even checking the qualifications of SOU’s new aviators. Both the government and the airline suffered embarrassment when it was revealed that one of the replacements didn’t have a proper license.

But the conflict continued, going on far longer than the union expected. It was both a costly and violent affair, with ALPA spending in excess of two million dollars, and fistfights between union members and strikebreakers taking place at airports. There was even gunfire during one incident involving a SOU substitute and his shotgun, resulting in an injured Delta pilot who was siding with ALPA.

The dispute was ultimately played out in the courts, as the union and the airline sued each other. President John F. Kennedy, who in part owed his election to the support of organized labor, created a commission to investigate the matter. During the proceedings, amidst revealing information concerning illegal bargaining maneuvers by SOU, it was disclosed that the U.S. government was actually backing the strike for the airline via federal funding—to the tune of nine million dollars. In mid-1962, after a favorable ruling for ALPA by the Civil Aeronautic Board (CAB), the union promptly appealed the decision. An unorthodox move, to say the least, but ALPA figured that SOU was going to do the same, and by beating the airline to the punch—filing with a court that would likely be more supportive of labor (the first court to receive an appeal has jurisdiction)—they increased their probability of victory.

In the meantime, ALPA pondered another way they could triumph. An approach first suggested during an early stage of the strike was now being seriously considered—the union could buy Southern Airways. ALPA had already acquired around twenty-two percent of the airline’s shares as part of an earlier tactic to get pilots into SOU stockholders’ meetings, and with the price of investment being relatively low due to the company’s low market value, it was worth contemplating. When word got back to SOU that an investment group had approached ALPA about selling thirty percent of the airline’s stock to the union, Frank Hulse capitulated. ALPA had prevailed.

In the meantime, ALPA pondered another way they could triumph. An approach first suggested during an early stage of the strike was now being seriously considered—the union could buy Southern Airways. ALPA had already acquired around twenty-two percent of the airline’s shares as part of an earlier tactic to get pilots into SOU stockholders’ meetings, and with the price of investment being relatively low due to the company’s low market value, it was worth contemplating. When word got back to SOU that an investment group had approached ALPA about selling thirty percent of the airline’s stock to the union, Frank Hulse capitulated. ALPA had prevailed.

Though the strike was the longest and priciest in the union’s history, lasting from 1960-1962, it was a fight ALPA needed to see through. Losing to Frank Hulse and Southern Airways would’ve weakened the union and set a dire precedent within the industry. But thanks to key strategies employed by Charles Sayen and those at the top, not to mention the resolve of its members, the pilots got what they deserved. The victory proved to be historic, and has paid off for union members working at smaller carriers ever since.

To learn more about the Southern Airways strike of 1960-62, see the recently opened George Hopkins Papers, which consists entirely of materials related to the walkout, as well as the ALPA President's Department Records, and the Clarence N. Sayen Papers. The collections are available to researchers at the Reuther Library.

Bart Bealmear is the Archivist for the Air Line Pilots Association (ALPA) at the Walter P. Reuther Library.

Reddit

Reddit Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn