Oral History Heroes: William V. Banks

William V. Banks seemingly did it all: he was a lawyer, minister, Freemason, businessman, and civic leader. He is perhaps best known as the founder of the United States’ first Black-owned and operated television station, WGPR-TV 62, and its sister radio station, WGPR-FM. In addition to all of these accomplishments, he was also known as an advocate for labor. In the 1930s, as the head of the Detroit arm of the International Labor Defense, he defended imprisoned striking workers in a business and social climate that was often hostile to organized labor and strikers.

William Venoid Banks (1903-1985) was born in Geneva, Kentucky. The son of a tenant farmer, he studied at the Lincoln Institute, Detroit City College (now Wayne State University), and the Detroit College of Law. He was admitted to the bar in 1930 and practiced law in Detroit until his retirement from practice in 1950. I had first become aware of Dr. Banks during a presentation about WGPR-TV at the Historical Society of Michigan’s 2015 Local History Conference. Panelists who had worked at the station recounted its history and Dr. Banks’ vision as its founder.

A year later, I was well into my term as Oral History Project Archivist at the Reuther Library. One of the collections I was describing was the Briggs Strike Oral Histories, an oral history project undertaken in 1975 by a Wayne State University graduate student to help document and understand this pivotal 1933 strike. Reading through the transcripts, a familiar name jumped out at me: William V. Banks. Though no mention of his media ownership made it into his oral history interview (nor had the conference panelists mentioned his labor affiliation), I wondered if it could be the same William V. Banks. A bit of online research was enough to confirm they were one and the same.

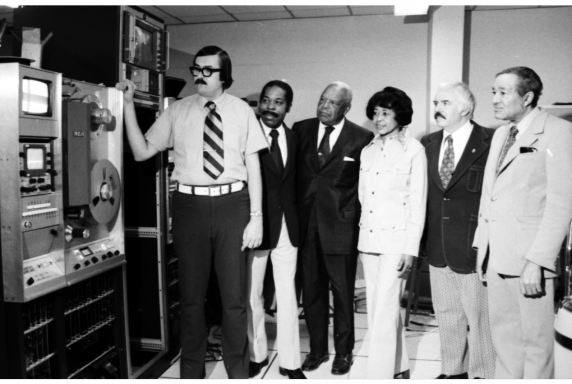

Dr. Banks operated both the radio station and the TV station with an eye not only toward serving Detroit’s African American community with relevant programming (an especially important community service in the years following 1967), but also with providing career and training opportunities. In fact, WGPR TV and radio became launching grounds for the careers of many African American broadcasters. In January 2017, a museum run by the WGPR-TV Historical Society opened on the site of the original station, on East Jefferson Avenue in Detroit, complete with a Michigan historical marker.

Connecting the dots in this way enriched Dr. Banks’ story for me, complicating the narrative of the crusading labor attorney. After all, Banks was once affiliated with a Communist organization and became a Republican business magnate. Yet this seeming conflict speaks to aspects of Dr. Banks’ character and work, an ethos he addressed in his interview, during which he states more than once that he doesn’t care about anyone’s political affiliation, but that he does identify strongly with working class people. He also expresses his disgust at the divide and rule mentality and tactics of the ruling classes. In his memoir, A Legacy of Dreams: The Life and Contributions of Dr. William Venoid Banks, edited by Sheila T. Gregory, he goes into more detail about his involvement and eventual falling out with the Communist Party, as well as many more details of his life and work.

Banks also focused on bringing in African American workers, whom he saw as targets both from exploitation by “the bosses” and the prejudices of their white co-workers. This attention on aiding the African American community is a connecting thread that runs through his life story, from his own disadvantaged upbringing in the South, to his work for the ILD, his involvement with black Freemasons organizations (including his founding of the International Free and Accepted Modern Masons, which provided community, business, and investing education and opportunities for its African American members), WGPR, and his work with the NAACP.

Dr. Banks’ work for the International Labor Defense is echoed today in lawyers defending imperiled immigrants and refugees. His observations and actions on class solidarity to transcend racial divisions, while at the same time recognizing the intersections of race and class through his targeted outreach of uplift to African Americans as a labor lawyer and later as a media mogul remains instructive as well. Moreover, his particular story forms part of a larger "hidden history" of struggle and self-determination, in which the working class radical left, including the African Americans allied with or part of the Communist Party, has fought for racial and economic equality and justice.

This concludes a three-part series of posts about the “oral history heroes” encountered by Rebecca Bizonet in her work as Oral History Project Archivist. The National Historical Publications and Records Commission (NHPRC) awarded the Reuther Library a two-year “Documenting Democracy” grant to provide and enhance access to our oral history holdings, which she has been doing by arranging, describing, and publicizing the interviews, including writing about some of the interviewees who have made a particularly strong impression on her.

Reddit

Reddit Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn