Folklore Friday: Irish Edition

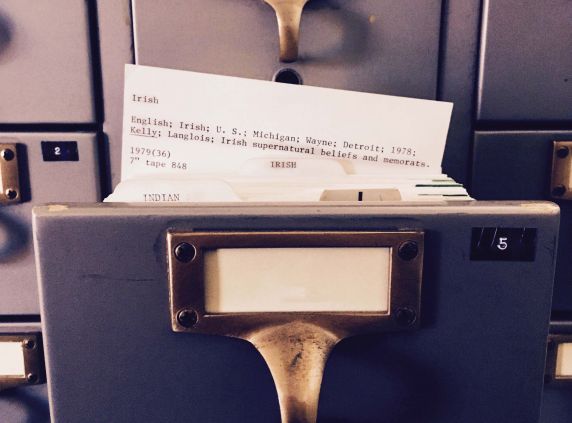

In honor of St. Patrick’s Day, this Folklore Friday we focus on the legends, beliefs, and traditions of the Irish, as recorded by students for their individual field projects.

Detroit, of course, was born as a French outpost and remained so for the better part of a century. However, the early 19th century brought new waves of immigrants, among them the Irish. For many Irish, ill at ease with the Protestant-dominated cities of the east and the violence and discrimination that went with them, Catholic Detroit was a welcoming destination. Detroit’s early Irish community was largely white-collar and settled on the Near East Side. The Potato Famine brought a surge in population to the city, and by 1853, nearly one in seven residents could claim ties back to Ireland. Forty-five percent of this population lived in the area now known as Corktown, the city’s oldest intact neighborhood. The population continued to grow as industry flourished and good wages drew new immigrants and settled emigrants from around the world.

Like so many groups before and after them, the Irish brought with them the legends and customs from the "old country." The representation of these traditions in the Folklore Archives include collections of legends, personal accounts, superstitions, songs, and beliefs gathered by students. The people interviewed are a mixture of people native to Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, as well as people whose families have been in the United States for one or more generations.

Like so many groups before and after them, the Irish brought with them the legends and customs from the "old country." The representation of these traditions in the Folklore Archives include collections of legends, personal accounts, superstitions, songs, and beliefs gathered by students. The people interviewed are a mixture of people native to Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, as well as people whose families have been in the United States for one or more generations.

We start with a sample of legends and legendary creatures, many of which may seem familiar. In her 1974 paper "Superstitions of the Irish" [1979 (103)], Elizabeth Hanson interviewed several men visiting Detroit from Northern Ireland. Jerry C., a musician from Belfast, shared the following:

"The Banshee is associated with the Irish, Welsh, and Scottish. Whenever anyone dies belonging to the Mac, Mc, or O’ Clans, the Banshee will appear before a family member to show that a death will occur. It appears as either as a small lady combing her hair –this is mainly Irish, or as a black cat –this is mainly Welsh or Scotch. It is identified by a wailing or cry. My Grandfather—my mother's father—heard a crying while he was outside his house—this was in the city. He reacted violently and came out with a brush and beat it on the wall. His father died two days later. This is a true story."

In addition to the story of the Banshee, Elizabeth also gathered a few other beliefs from Jerry:

"The pouka is another superstition Jerry told me about. The pouka is an oversized dog which cannot cross water. It is supposed to be the devil in animal form and is seen at certain times of the year—especially in the winter. It never attacks, but it blocks the way. You cannot pass it. The best way to rid yourself of it is to cross water. Even though Jerry has never seen one, his friend Johnny once came across one. It is also tradition to leave three glasses of water for the souls on All Souls Night. Jerry's grandmother did this. During the night she would hear chairs being moved about and in the morning she would find that the water had been drinken....Jerry explained these supernatural phenomenon as "lamentations" created by a spirit—the energy left behind by a body after it goes.

When I asked Jerry about leprechauns he hysterically answered "Don't call them leprechauns! They are called Fairoids." Fairoids were the original race of Ireland who were driven below ground. They were ordinary people but were small—2.5 to 3 feet tall. They are said to have psychic powers and they spoke Gaelic (Irish). The Fairoids developed into the idea of fairies. I asked Jerry if you caught one would you get a wish and he said no. He believes that leprechauns are a commercial gimmick. I asked Jerry about four leaf clovers but he had never heard about them bringing you luck until he came to the United States."

John M., also a musician from Belfast, spoke to Elizabeth of the blackthorn bush and a tradition practiced by farmers in the "South" (Republic of Ireland). He claimed that it was common for farmers to leave a single blackthorn bush undisturbed in the middle of a field when preparing the land for harvest. The bush is for fairies to live in—if their home is cut down the fairies will bring bad luck.

But what exactly are fairies? In Rosemary Jordan’s 1979 paper "Irish Legends" [1980 (56)], fairies, and in turn Banshees, are explained by Mrs. N, a native of Ballina, County Mayo, who grew up next to a "fairy dwelling":

"You see, a fairy is really a fallen angel. It is not good enough to be in heaven, but not bad enough to go to the hot spot. Fairies are usually friendly and helpful unless you trespass on their property....fairies are playful. It's Banshees that are dangerous. Banshees are lamentable characters. They were snobs and only bothered the oldest and best-bred families. They always wail before a member of such a family dies. Unfortunately, we had two rich families in the area while I lived at home and I heard a Banshee wail four times. Three out of the four times, someone from one of those

families died."

For additional tales of fairies, Banshee, poltergeists, and ghosts, we recommend Pat O' Dowd’s 1979 paper "Irish Superstitions and Divination" [1980 (33)]. In it, O’Dowd interviews his mother Anne Marie Lee Brown, who shares lore she remembered from a childhood spent in Kilkkerrin, County Galway at the beginning of the twentieth century. The transcript of this conversation is attached to the bottom of this blog as a pdf.

Irish Folk beliefs and superstitions, whether developed in Ireland or in the United States, are present throughout the collection. The following are examples drawn from several field projects, including Madeline Heffron’s 1945 paper “Workshop in Folklore" [1945 (17)], Elizabeth Hanson’s "Irish Legends" [1979 (103)], and Jacquelyn Bernstein's’ "Historical Study of Lore in the Middle West" [1967 (66)].

- "For butter that will not come: Iron of every kind keeps away malignant fairies. Thus a horseshoe nailed to the bottom of the churn keeps the butter from being bewitched."

- Throw a candlestick on Candlemas Day to celebrate the end of the dark days of winter.

- Leave a pail of water on the stoop every night for a Banshee to drink. You will know she has been there if there are hairs floating in it. Also, never throw your dishwater out the back door at night, for if you hit a Banshee with it you will have bad luck.

- When you go to an Irish Wake, take your pipe and fill it with tobacco there in the house. Every time you smoke that pipe you owe the departed one a prayer.

- Always wash your hands when returning from a funeral.

- If you look over your left shoulder at the full moon it will bring very good luck.

- If you sing at the table it will bring bad luck. The only way to remove the curse is to stand up.

- If you drop a fork you are going to come into some money. If you drop a spoon

someone will visit. - If you see a white dove over the water that means a loved one will pass into heaven soon.

- If you rock a rocking chair with no one in it you will have bad luck.

- Keep the window shut in a baby’s room, or its soul may escape.

Personal narratives of life in Ireland are found in several collections, however nowhere as charming as the interview with "Mr. T and Mrs. N" by Rosemary Jordan in her 1979 paper "Irish Legends" [1980 (56)]. Whether they are discussing the dangers of running through a fairy fort, ghosts, or the intervention of St. Patrick, the brother and sister duo give a light, conversational account of the lives they led in Ballina, County Mayo, near the turn of the century. Not all of their accounts deal with the supernatural, however. One of their more interesting (and somewhat funny) remembrances deals with Mr. T’s failed attempt to join the Fiannas, an organization notably active during the Irish War of Independence and the Irish Civil War:

Mrs. N: Mr. T, do you remember when you tried to get into the Fianna?

Mr. T: Boy do I ever!

Mrs. N: But of course you never made it. Too bad—you would have been a credit to the group.

Mrs. M (the sister-in-law of Mrs. N and Mr. T): Wait a minute, who are the Fianna?

Mrs. N: Well, they were a volunteer group in Ballina who helped the Civil Guards. But of course they had to pass certain tests, which Mr. T failed.

Mr. T: OK, Mrs. N, that’s enough.

Mrs. N: Well, the Fiannas were based on a band of warriors long ago, led by a famous hero, Finn MacCool. He fought some Spaniard gents and saved Ireland for the Gaelic Celts. To qualify for membership back then, a recruit had to memorize ten books of poetry and….

Mr. T: Twelve books, Mrs. N.

Mrs N: Sorry twelve books of poetry, and also run through a thick forest leaping over branches as high as his forehead and stooping under limbs as low as his knees without breaking a twig or tearing off a leaf. And of course, he had to pull a thorn out of his foot without breaking his stride.

Mr. T: No, no! All I had to do was make it through this forest in Ballina and I could have passed the test. But of course, the forest had booby traps and I slipped on one of them, hit my head against a tree and split my pants. The rest of the group had to find me and escort me out. I was dazed and dirty and felt really awful. I was supposed to fight another recruiter as the last part of the test, but this guy won easily because I didn’t really know what I was doing. Needless to say, I did not become a member.

Mrs. N: And you should have seen him when he came home. My, my what a sight!

We would be remiss to end this Folklore Friday without a mention of St. Patrick’s Day, the holiday that unites most Americans, at least a little bit, as Irish. The lore of St. Patrick, patron saint of Ireland, is touched on briefly in several projects, however, none so much as Karen Ellsworth’s "St. Patrick’s Day Lore" [1980 (43)]. In her 1979 project, Ellsworth surveyed several dozen people of various ethnic backgrounds from around the metropolitan area and asked them what they knew about the background and symbols tied to the holiday and Irish Culture. The results, often humorous, give insight into how well understood the holiday was before the mass commercialization of recent years. The survey is too lengthy to share here, however, it is open for research through the Reuther Library’s Reading Room.

We will leave you with this toast in case you are in need of one this St. Patrick’s Day. Sandra Lynn Nelson collected it from Shey Patrick McDowell for her 1969 project, Irish-American Drinking Lore [1969 (82)]:

The Toast*

Slan agus seaghal agat; / Health and life to you;

Bean ar mhein agat; / The woman of your choice to you;

Talamh gon chios agat; / Land without rent to you;

Agus bas in Eirinn. / And death in Ireland.

Sláinte, to you all!

For more information about the Folklore Archives, please contact a Reuther archivist through reutherreference@wayne.edu, or visit us in our Reading Room during normal business hours, Monday-Friday, 10:00 a.m.-4:00 p.m.

*Note: The misspelling of Irish words in The Toast is likely the result of it having been written down phonetically by a non-native speaker.

Folklore Fridays is an exploration of a theme or topic found within the Folklore Archive through text, audio, or still imagery. It appears on the Reuther Library blog on a Friday of each month. The Folklore Archive, established in 1939, contains the oldest and largest record of urban folk traditions in the United States.

Elizabeth Clemens is an Audiovisual Archivist at the Walter P. Reuther Library.

| Attachment | (click to download) | |

|---|---|---|

| O_Dowd.pdf | 579.65 KB |

Reddit

Reddit Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn