Remembering Martin Luther King, Jr.

“It is a crime to live in this rich nation and receive starvation wages.”–Martin Luther King, Jr.

At the beginning of 1968, working conditions for sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee, especially African Americans, were atrocious. Employees were given no benefits, no vacation pay, no pensions; forty percent qualified for welfare, and many worked second jobs. During bad weather, black workers were sent home without pay, while white workers collected a full day’s wages. The Memphis Sanitation Department refused to modernize the equipment used by black workers.

On February 1, 1968, during a storm, two black sanitation workers, Echol Cole and Robert Walker, took shelter from the rain inside the back of a garbage truck. An electrical short in the truck’s wiring caused the compressor to start, and the two workers were crushed to death. On February 11, T.O. Jones, president of the as-yet-unrecognized AFSCME Local 1733, called a meeting where members voted to strike.

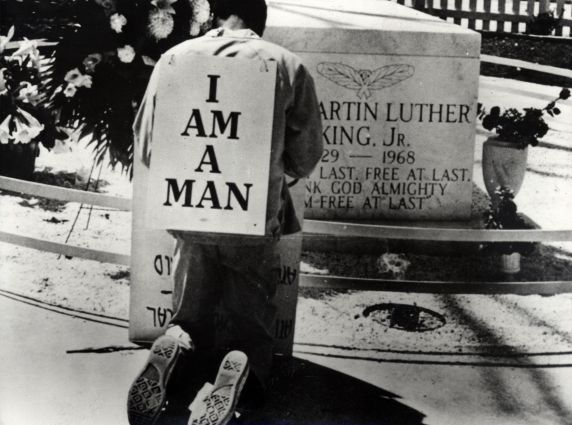

AFSCME International officials William Lucy, P.J. Ciampa, and President Jerry Wurf, soon arrived in Memphis to help with negotiations. Talks with Mayor Henry Loeb’s administration were unsuccessful. On February 23, strikers and supporters marched carrying signs with the simple message “I AM a Man.” The march ultimately turned violent, with police using mace on marchers. After this incident, the Memphis community, led by local ministers, gathered around the strikers, forming the Community on the March for Equality (COME).

COME leaders contacted national civil rights leaders to come to Memphis to help with the cause. NAACP President Roy Wilkins, Bayard Rustin, and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. arrived in Memphis in mid-March 1968. Dr. King spoke to 10,000 strikers on March 18. He returned on March 28th to lead a march, but within minutes of beginning, violence erupted again. Dr. King vowed to return to lead a peaceful march.

On April 4, 1968, Dr. King was resting in the Lorraine Motel in Memphis following a series of meetings about the strike. Just before dinner, Dr. King went onto the balcony to greet supporters where a sniper’s bullet took his life. After a large, memorial march on April 8, strikers returned to the bargaining table, determined that Dr. King’s life should not have been given in vain. On April 16, city officials formalized a strike settlement that included a fifteen-cent per hour raise and an end to racial discrimination within the work place.

Dr. King believed that racial equality and economic equality are inherently linked, and that economic equality and labor rights are also civil rights. He was a strong supporter and ally for the labor movement. In this vein, current day labor leaders chose April 4, 2011, 43 years after Dr. King’s death, as a day of solidarity and protest in response to anti-labor legislation brought forth in Wisconsin, Ohio, Michigan, and a number of other states. The fight for which Martin Luther King, Jr. gave his life continues today.

Johanna Russ was the Archivist for the American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) from 2008 until 2013.

- jruss's blog

- Login to post comments

- Printer-friendly version

Reddit

Reddit Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn