1968 Memphis Sanitation Workers and Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Thomas Oliver “T.O.” Jones believed a union for sanitation workers in Memphis, Tennessee was a necessity. A sanitation worker himself, he experienced the unfair working conditions and accompanying low pay. It was the 1960s and forty percent of full-time Memphis sanitation workers qualified for welfare assistance. The men had to carry heavy trash bins, often leaking waste, from residents’ yards to the trucks in sweltering Memphis heat. Black workers did not have access to bathrooms, showers, or uniforms. The city failed to properly maintain their equipment and malfunctions proved disastrous.

As early as 1959, Jones fought to form a union. He faced difficulty recruiting members, however. Few could afford to lose their jobs - a real threat to anyone trying to organize. But Jones persisted and with the help of established labor unions in the area he slowly rallied a following.

In June of 1963, Public Works Commissioner William Farris fired 33 sanitation workers, including Jones, who had attended a union meeting. The city later rehired 32 of them, after an appeal from community leaders, on the condition they cease union activity. Jones refused and instead forged ahead with organizing. He successfully secured support and a charter from the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) in 1964. They chose local number 1733 in honor of the 33 men fired the previous year. With AFSCME in their corner, Jones and his compatriots became bolder, though they still had a long road ahead of them.

A new mayor and public works commissioner did not make things easier on Local 1733, despite campaign promises stating otherwise. Henry Loeb began his second mayoral term in 1967. As former public works commissioner, Loeb insisted he supported the workers’ cause and he would take care of them. Therefore, he reasoned, they did not need a union. As Loeb repeatedly refused to recognize or negotiate with Local 1733, the workers’ frustration increased. The situation escalated on February 1, 1968, when two men lost their lives.

Echol Cole and Robert Walker took shelter from the rain – already a hazardous working condition – in the back of their sanitation truck. An electrical short triggered the compactor crushing the two men to death. On top of their families’ grief, the city offered little recompense.

On February 11, union members voted to strike.

Representatives from AFSCME International soon arrived to back their local. William Lucy, then Assistant to the President; PJ Ciampa, International Field Staff Director; and Jesse Epps, International Representative, came to Memphis to support the strike. When the stakes became clearer to the International, AFSCME President Jerry Wurf himself arrived.

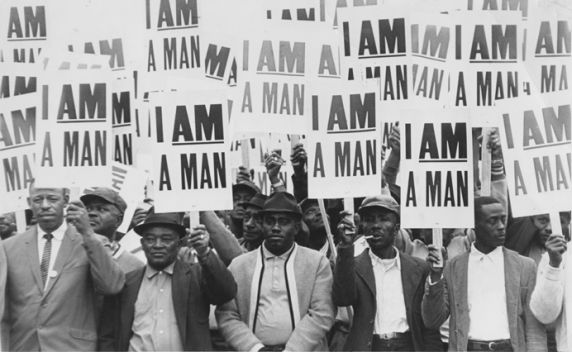

The demands were, in part, typical of other strikes. The men wanted raises, union recognition, and dues deduction. Ultimately, however, the strike demanded something more – the men wanted to be treated as human beings, every bit as worthy as their white co-workers, and afforded dignity and respect. The slogan “I AM a man” became the theme around which workers and the community rallied.

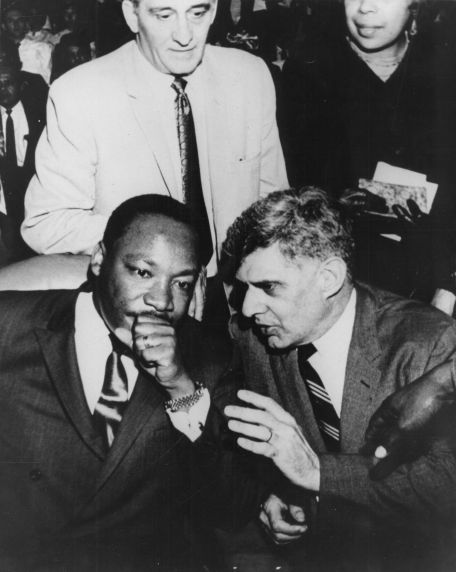

That community was crucial to the strike effort. Religious leaders like Rev. James Lawson and community activists like Cornelia Crenshaw lead support efforts. It was Lawson who reached out to Martin Luther King, Jr., changing the course of the strike and ultimately the Civil Rights Movement.

The Memphis strike illustrated the racial and economic justice pillars of King’s Poor People’s Campaign. He traveled to Memphis to support the sanitation workers and with his presence came a national spotlight. In an address to the 1300 men he said, “You are reminding, not only Memphis, but you are reminding the nation that it is a crime for people to live in this rich nation and receive starvation wages.”

On April 3, at Mason Temple, King gave his famous “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech. The next day, an assassin ended his life at the Loraine Hotel.

Sanitation workers, along with other union members and civil rights leaders from across the country, silently marched the streets of Memphis for King’s memorial, led by Coretta Scott King.

On April 12, the city agreed to recognize the union. The Memphis Sanitation Workers Local 1733 won their first contract.

A few months later, AFSCME held a memorial for King. Speakers included Jerry Wurf, Rev. Ralph Abernathy, and Coretta Scott King. King spoke of her husband’s legacy and called for his work to be carried on: “I know that all of you will be working together with those of us of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference to help bring his dream to full fruition.”

“We are all debtors to society,” she said. “Martin Luther King, Jr. paid his debt and now through his legacy, we are challenged to pay ours.”

AFSCME still represents sanitation workers and others in Local 1733. Present day AFSCME leaders, along with community and civil rights leaders from Memphis and across the nation, will mark the 50th anniversary of the strike and King's death in Memphis as a call to action for the causes of racial and economic justice. The legacy of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the Memphis sanitation workers is as strong as ever 50 years later.

To learn more, see the Reuther's online exhibit, I AM a Man.

Stefanie Caloia is the Archivist for the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees.

Reddit

Reddit Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn