Joe Hill, the Man Who Never Died

In the Winter 2013 semester, the Reuther Library worked with students in the Graduate Certificate in Archival Administration program at the Wayne State School of Library and Information Science to produce a series of student-written, guest blog posts.

Robert Kett is a second-year SLIS student and amateur musicologist with a genuine interest in labor history and especially labor songs.

A pamphlet, no matter how good, is never read more than once, but a song is learned by heart and repeated over and over.

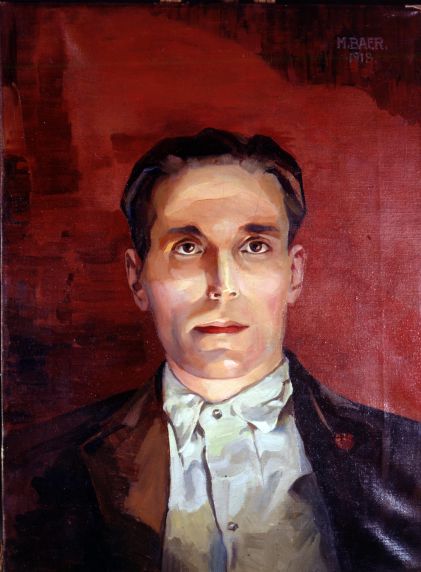

-Joseph Hillstrom, 1879-1915

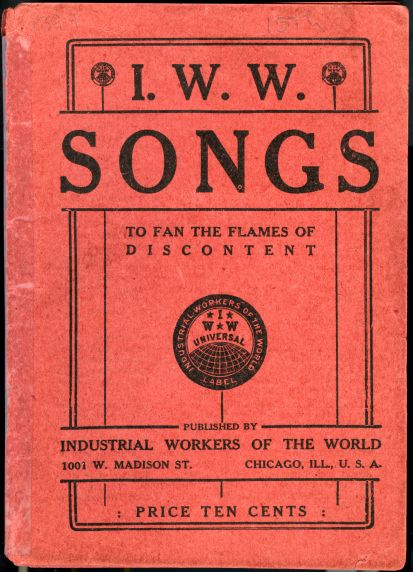

Among the strongest tools in the hands of the American labor movement is the labor song. Labor songs serve to inspire, rallying calls for the downtrodden fighting against immensely powerful forces. The Industrial Workers of the World, more familiarly the Wobblies, a union founded in 1905, was particularly enamored with the labor song; the first edition of their Little Red Songbook was published in 1909 in Spokane, Washington. Two years later came the inclusion of the first compositions of a Swedish immigrant named Joseph Hillstrom, better known as Joe Hill, in the Songbook. Hill quickly emerged as among the best songsters in the IWW, which Hill had joined around 1910. One member of the union reacted to Hill’s first labor songs, “The minute he appeared with his first and then his second song, we all knew he was the great one.”

Born Joel Emanuel Hägglund in Gävle, Sweden in 1879, Joe Hill immigrated to the United States in 1902. An itinerant worker, he found work stacking wheat, laying pipe, digging copper, picking fruit, on docks and in smelters, and playing piano and sweeping up in a Bowery saloon. He moved west, from New York to Cleveland and eventually to the West Coast. Inspired by a strike involving Southern Pacific workers, Hill composed a parody of the traditional “Casey Jones,” turning the brave Illinois Central engineer into a Southern Pacific scab sent to Hell for working during the strike. The striking workers who overheard the song as it was being composed liked the finished parody enough to print it on cards to be passed along the union vine. Before long, “Casey Jones, The Union Scab” was being sung nationwide, and Hill had found a calling.

Between 1911 and 1913, Hill’s pen poured out classic labor song after classic labor song, among them “The Preacher and the Slave,” “Mister Block,” “Scissor Bill,” “What We Want,” and “There is Power in a Union.” Alternately set to traditional and original music, the songs were heard on picket lines and in organizing meetings of miners, lumberjacks, railroad workers, hop pickers and more. Hill was equally adept at composing general songs and those focusing on specific events. A leading contributor to the Little Red Songbook over the course of these years, eventually, a quarter of the songs in the standard edition of the songbook would be written by Joe Hill.

Hill moved to Utah in late 1913 with little more than his songbook. The events of January 10, 1914 would forever alter the life of Joe Hill and make him a labor martyr.

That night, grocer John Morrison and his son, Arling, were shot and killed in Salt Lake City. The two men who witnesses saw fleeing were around 5 feet, 9 inches tall and 155-160 pounds, shorter and heavier than the 6 feet tall, 140 pound Hill. The same night, Hill, with a bullet wound to the chest, went to a doctor’s home stating that he had been shot while arguing over a woman. One of four men treated for bullet wounds in Salt Lake City that night, this coincidence made Hill a prime suspect in the Morrison murders.

Upon seeing the songsmith, the murder’s only witness, 13-year-old Merlin Morrison, was reputed to have said “that’s not him at all,” but over the course of the subsequent trial, the young boy retracted the statement. No witness positively identified Hill, though some stated he bore a resemblance to one of the men seen fleeing. Specifics on the trial are difficult to come by as many of the court records vanished over time.

What is known is that the evidence against Joe Hill was largely circumstantial and that his refusal to testify and problems with his legal representation plagued Hill throughout. The prosecution triumphed; Hill was convicted and sentenced to die by firing squad. Sympathizers and defenders believed that he was framed due to his IWW membership, blaming the Mormon church and the “copper bosses.” Attempts from prominent figures and groups (among them President Woodrow Wilson, fellow Wobbly Helen Keller, the Swedish Ambassador to the United States, and the American Federation of Labor) to call on Utah Governor William Spry to commute Hill’s sentence fell on deaf ears, with Spry’s only response that he desired to rid Utah of the Industrial Workers of the World. On November 19, 1915, the sentence was carried out. One of his last telegrams, written to IWW leader Bill Haywood, stated in part “…don’t waste any time mourning. Organize!” Hill’s final will, handed to a prison guard hours before his execution, quickly became heralded as a prized poem for the American labor movement.

My will is easy to decide,

For there is nothing to divide.

My kin don't need to fuss and moan --

"Moss does not cling to a rolling stone."

My body? Ah, If I could choose,

I would to ashes it reduce,

And let the merry breezes blow

My dust to where some flowers grow.

Perhaps some fading flower then

Would come to life and bloom again.

This is my last and final will.

Good luck to all of you.

-Joe Hill, November 18, 1915

Hill’s bullet-riddled body was sent to Chicago where Haywood gave his eulogy.

Joe Hill served as an inspiration to future generations. During the Great Depression, “The Preacher and the Slave” found new life as an anthem for the down and out. In 1930, Alfred Noyes composed the poem “I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night”; six years later, Earl Robinson set the poem to music, and a folk standard was born. In 1958, Hill was honored with an off-Broadway play, The Man Who Never Died. He is heralded as a hero by Communists, Socialists, the American Federation of Labor, and generations of singer-songwriters. Among the prominent singer-songwriters he influenced were Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger, Tom Paxton, and Phil Ochs, all of whom are represented in the People’s Song Library Records.

Those researching Joe Hill himself can find a wealth of documents in the Joe Hill Papers, the People’s Song Library Records, the John Beffel Papers, the Richard Ellington Papers, the Frederick W. Thompson Papers, and especially the IWW Records.

Additional Bibliography:

Adler, William M. The man who never died: the life, times, and legacy of Joe Hill, American labor icon. Paperback ed. New York: Bloomsbury, 2012.

Stavis, Barrie. “Joe Hill: Poet/Organizer,” Folk Music, July-August 1964

Stegner, Wallace. “Joe Hill: The Wobblies' Troubadour,” New Republic, January 5, 1948

- Public Relations Team's blog

- Login to post comments

- Printer-friendly version

Reddit

Reddit Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn