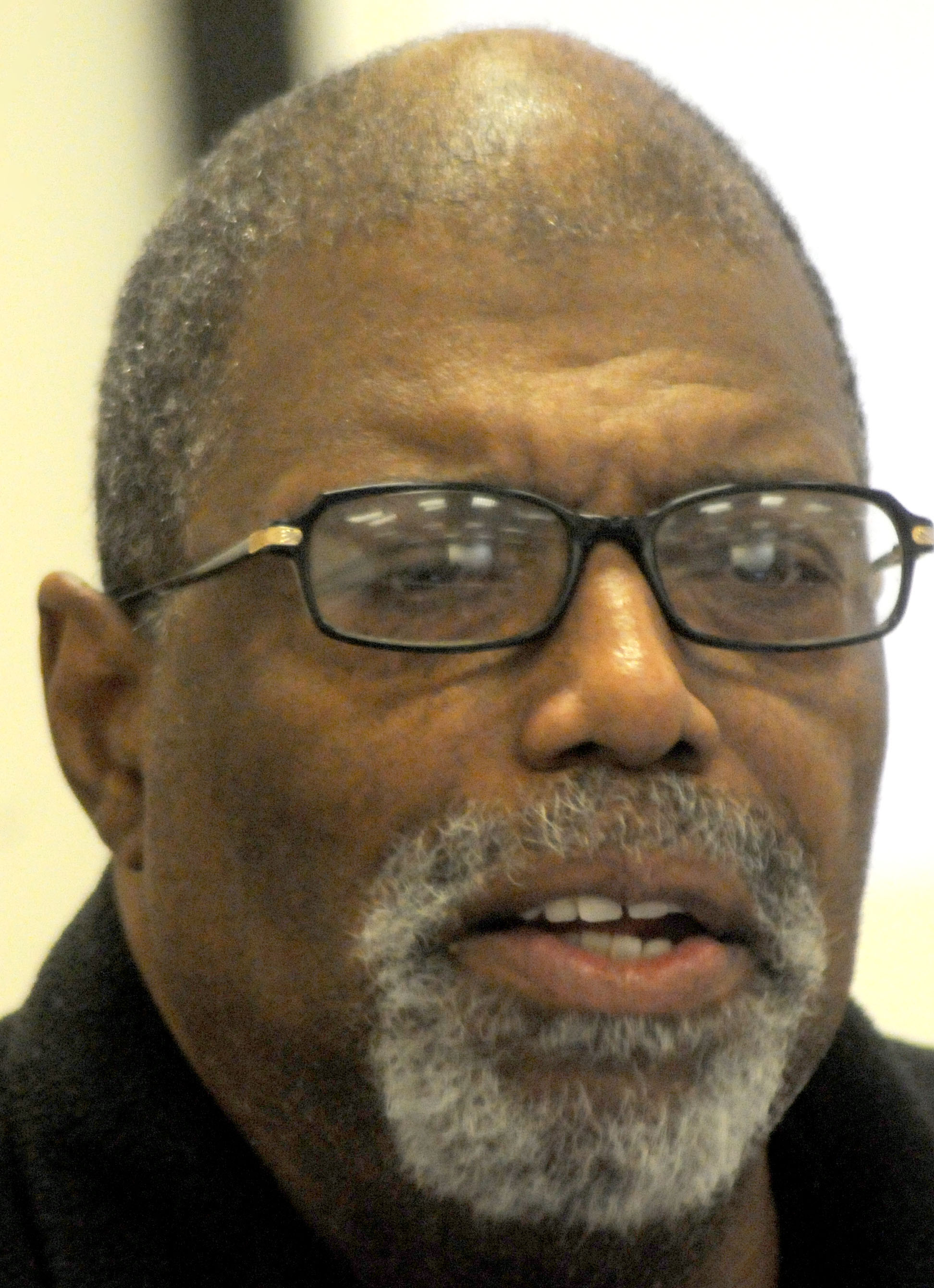

General Gordon Baker, Jr.: A Detroit Revolutionary to the Core

There is a select group of people who place the needs of others above their own, do so against formidable forces and at great risk to their own welfare and well-being. They take these risks never knowing exactly how they will fare, but recognizing that their convictions demand that they cannot do otherwise. General Gordon Baker, Jr., a Detroit revolutionary, was among this select group of people. On May 24, 2014, a packed audience at Dearborn, Michigan’s UAW Local 600 memorialized his life that ended six days before. It was there that attendees gave tribute to a man whose impact did not pass with his death.

Baker was born in 1941 to parents who had migrated to Detroit shortly before his birth. His family was part of the great migration of people who came to Detroit and other northern cities in search of work in waves beginning with the outbreak of WWI and extending into the 1960s. An intellectual and activist who understood working class people and their struggles, Baker was without pretense and was a part of this segment of the population for which his words and actions gave voice.

His activities are too numerous to list here, but it is worth noting that each effort he pursued drew from previous experiences. At Wayne State University, Baker founded the Black activist student organization UHURU meaning “freedom” in Swahili. From there, he joined with others associated with the Inner City Voice, which led the effort to organize the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement (DRUM), which sought to address the poor treatment Black workers received at Chrylser’s Dodge Main plant. DRUM also took aim at the UAW for what it considered a lack of viable Black UAW staff members, leaders and priorities directed toward Black workers subjected to poor working conditions and pay.

Out of DRUM came the League of Revolutionary Black Workers that served as an umbrella organization for other organizations representing Black workers within the auto industry and elsewhere within the city. Speed ups and other poor working conditions, some of which led to the deaths of Black workers, motivated Baker and others to continue their fight. These speed ups made Chrysler a rich company at the expense of their workers, especially Blacks who worked in some of the most dangerous and lowest paying jobs. Their weapon was the wildcat strike, which they used with some success. Along the way, Baker developed a class analysis allowing him to link capitalism with racism, which in turn, dictated the way he approached the problems Black workers experienced in the auto plants and elsewhere. DRUM and the League were only in existence from the late 1960s to the early 1970s, but their impact was meaningful, which many within the UAW came to acknowledge in subsequent years, although the UAW viewed Baker and others associated with him as a threat during their more active years.

Baker was, of course, not alone in the development of this analysis or activism. Mike Hamlin, Ron March, Luke Trip, John Watson, Ken Cockrel, Sr., John Williams, Chuck Wooten and Baker’s wife Marian Kramer-Baker, amongst many others, worked with him at varying moments to transform Detroit.

copy.jpg)

In the course of his activism, he was fired from the Chrysler Dodge Main plant and Ford Motor Company. Likewise, his commitment and dedication to his convictions meant that it was easier for him to refuse enlistment into the military during the Vietnam War rather than sacrificing his beliefs. This he did, even before Muhammad Ali famously refused to serve in the military two years later. The threat of imprisonment for booing the National Anthem to protest Detroit’s bid to host the Olympics because of the city’s refusal to pass a meaningful open housing law also reflects the depth of his convictions. Similarly, he traveled to Cuba with a group of revolutionary-minded students, never fearing the repercussions of traveling to a country the U.S. government had officially barred its citizens from visiting two years before. It was from his experience in Cuba that he combined elements of Black nationalism with Marxism despite the trend to adhere to a strain of civil rights that he believed to be too gradualist and ineffective. Most strikingly, a bullet that many thought was meant for him, left Fred Lyles, a tenants’ rights activist, permanently paralyzed. A voluminous FBI file did not deter him from seeking, albeit unsuccessfully, election to the Michigan State House of Representatives.

The Reuther Library is the home to a number of resources that document Baker’s earlier work and thoughts as an activist. In fact, these resources are some of the most widely used at the Archives. Among them are the collections of the Detroit Revolutionary Union Movement; the papers of Ken and Sheila Cockrel, which contain records of the League of Revolutionary Black Workers; and the Dan Georgakas Papers, which contain material that Georgakas used while writing his book Detroit: I Do Mind Dying, which chronicles the history of DRUM and the League of Revolutionary Black Workers. The Archives also holds a number of issues of the Inner City Voice with which Baker was closely associated as well as the documentary film, Finally Got the News, which is also about the work of DRUM. As the UAW once considered him and the organizations with which he was closely aligned as a threat, they kept records that reveal how they once viewed him and those organizations. Relevant UAW records are now housed in collections of the UAW Local 3, Region 1, as well as UAW president Walter Reuther and Leonard Woodcock.

- UAW Local 3

- UAW Region 1

- UAW President's Office: Walter P. Reuther Records

- UAW President’s Office: Leonard Woodcock Records

In more recent years, Baker played a significant role in Retirees for Single Payer Health Care, the Highland Park Human Rights Coalition, the Black Men in Unions, UAW Local 600, the League of Revolutionaries for a New America, for which he was the founder and President, welfare rights organizations where his wife Mariam Kramer-Baker serves in prominent roles and, most importantly, within his immediate and extended family where his commitment to his wife, children, grandchildren and many others speak volumes about the depth of his love and character. Wayne State University’s Archives of Labor and Urban Affairs welcomes the opportunity to talk with people about collecting the records of these entities and others with which Baker was affiliated in order to make them available to scholars and journalists writing books and articles, museum professionals curating exhibits, filmmakers producing documentary films and students preparing papers for undergraduate assignments, as well as graduate level theses and dissertations. If you think you have records documenting Baker’s life or that fit elsewhere within the Reuther Library Collection Policy, please contact the field archivist Louis Jones at 313.577.0263 or Louis.jones@wayne.edu. With your help, we can better ensure that our diverse range of researchers can provide exposure to the work of Baker and many others whose contribution to the historical development of organized labor and metropolitan Detroit receives the attention it deserves.

A second memorial tribute for Baker will be held at the Charles Wright Museum of African American History in Detroit on Saturday, September 6 from 6:30pm until 9:30pm. It is free and open to the public.

This blog post was largely derived from Dan Georgakas and Marvin Surkin, Detroit: I Do Mind Dying (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1975); “General Baker,” interviewed in Robert H. Mast, ed., Detroit Lives (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1994), 305-313; Heather Thompson, Whose Detroit? Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City (New York: Cornell University Press, 2001), 159-191; and David Goldberg, “Detroit’s Radical,” Jacobin: A Magazine of Culture and Polemic. I’d like to thank Marian Kramer-Baker and David Goldberg for providing additional information for this article.

| Attachment | (click to download) | |

|---|---|---|

| General_Baker_1.jpg | 729.57 KB | |

| General_Baker_2.jpg | 116.42 KB |

- ljones's blog

- Login to post comments

- Printer-friendly version

Reddit

Reddit Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn