Women Engineers Moved the Midcentury Motor City

While the number of women in engineering increased dramatically between 1900 and 1950, the actual number of women in engineering was still quite small: approximately 3,000 women, or just two-tenths of one percent of working engineers in the United States. Detroit's automobile industry presented a growing number of opportunities for women in engineering, however, and local papers in the 1950s and 1960s frequently published articles about these female curiosities in what was still very much considered "a man's world." The stories of Society of Women Engineers Detroit Section members provide a fascinating look at the opportunities and challenges faced by midcentury women engineers as they thrived–or not–in the Motor City.

While the number of women in engineering increased dramatically between 1900 and 1950, the actual number of women in engineering was still quite small: approximately 3,000 women, or just two-tenths of one percent of working engineers in the United States. Detroit's automobile industry presented a growing number of opportunities for women in engineering, however, and local papers in the 1950s and 1960s frequently published articles about these female curiosities in what was still very much considered "a man's world." The stories of Society of Women Engineers Detroit Section members provide a fascinating look at the opportunities and challenges faced by midcentury women engineers as they thrived–or not–in the Motor City.

Virginia Sink

Mary Virginia Sink was born in 1915 and grew up in Denver, Colorado. She enrolled in engineering at the University of Colorado, believing that would help her teach mathematics and science. She soon discovered that she could not afford the graduate studies necessary for a teaching certificate, and abandoned her teaching plans entirely in favor of a career in chemical engineering. She was one of just three women in her engineering class at the University of Colorado, and was the only one to graduate. She faced some skepticism, telling the Colorado Alumnus newsletter in 1966 that she had to convince peers and professors that she was "after an engineering degree, not an engineer." Nevertheless, in 1936 she received a degree in chemical engineering from the University of Colorado with special honors, as one of the top three students in her class.

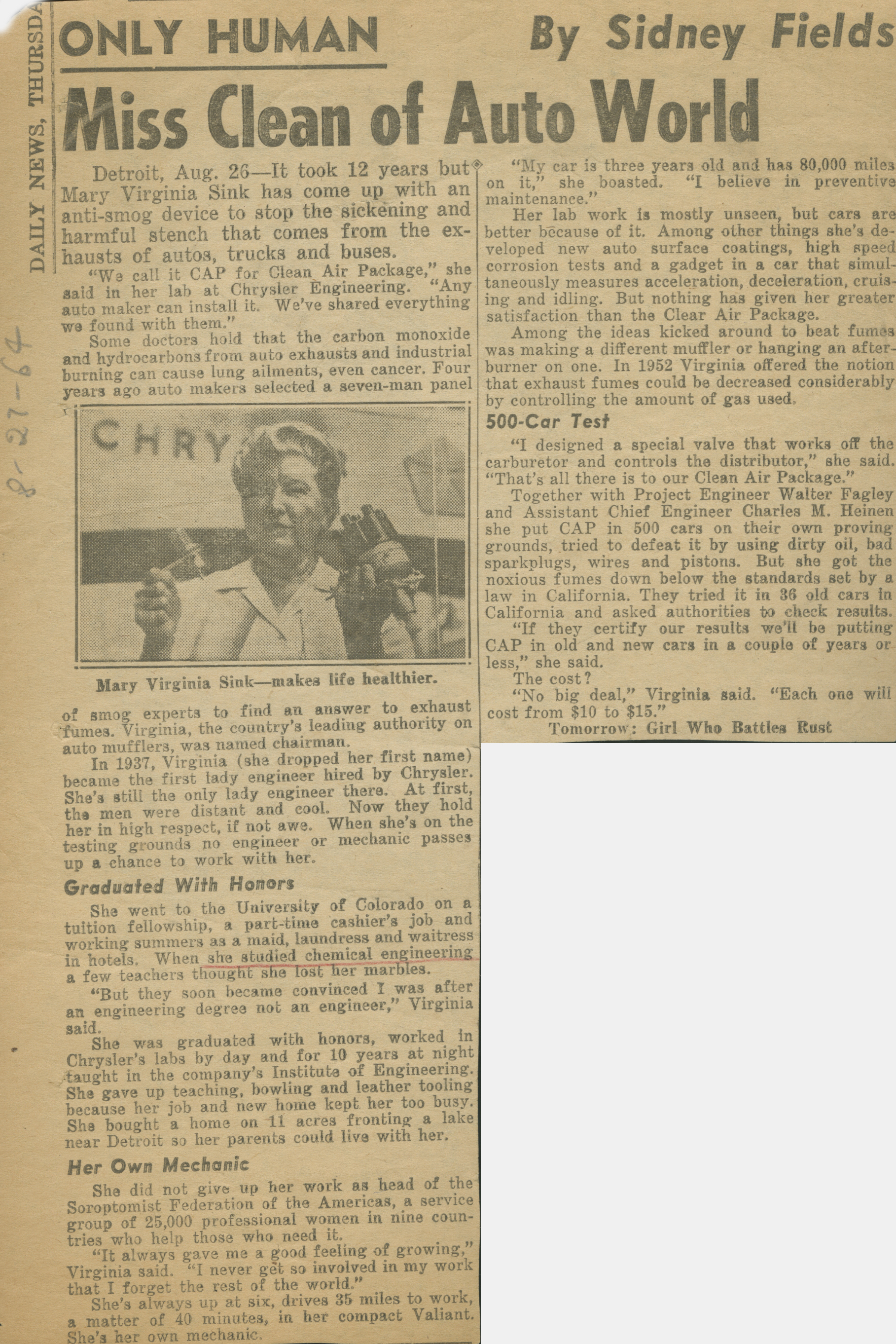

Sink was recruited by Chrysler Corporation and brought to metro Detroit as a laboratory engineer in the company's materials testing department, becoming the nation's first female automotive engineer. Among her first assignments was to establish Chrysler's Spectographic Laboratory to determine impurities in its zinc die casting alloys. She took night classes at the Chrysler Institute of Engineering and graduated at the top of her class in 1938 as the first woman to receive master's degree in engineering there. She continued working for Chrysler Corporation during the day and teaching night classes at the Institute until 1946.

In 1943 Sink was named Supervisor of Laboratory Personnel and placed in charge of a recruiting and training program for high school girls to fill engineering jobs during the Second World War. Between 1943 and 1945 she recruited 500 women, although very few remained in their positions following the war. Sink herself returned to technical work after the war as a project engineer and supervisor of spectrographic and radiographic laboratories. In 1950 she was named the Group Leader in Chemical Research Department, and over the next several years developed "infrared spectrography as a tool for analysis of smog producing chemicals." Two years later, in 1952, Virginia Sink became a charter member of the Society of Women Engineers Detroit Section.

In 1943 Sink was named Supervisor of Laboratory Personnel and placed in charge of a recruiting and training program for high school girls to fill engineering jobs during the Second World War. Between 1943 and 1945 she recruited 500 women, although very few remained in their positions following the war. Sink herself returned to technical work after the war as a project engineer and supervisor of spectrographic and radiographic laboratories. In 1950 she was named the Group Leader in Chemical Research Department, and over the next several years developed "infrared spectrography as a tool for analysis of smog producing chemicals." Two years later, in 1952, Virginia Sink became a charter member of the Society of Women Engineers Detroit Section.

From 1957 until 1962 Sink was sent on special assignment to the Los Angeles Smog Project. She served as Chrysler's representative and chaired the cooperative committee of the Big Three automotive companies to analyze the contributions of automobiles to Los Angeles smog and identify preventative measures including offburners and catalytic mufflers. With two colleagues she developed Chrysler's Cleaner Air Package in1962, emissions control technology that predominated in Detroit automotive companies until a congressional mandate in 1972 called for the use of catalytic converters. Sink retired 1979 as the Manager of Emission Certification in the Materials Engineering department, after 42 years, 6 months, and 6 days with Chrysler.

Sink was extraordinarily active in a number of professional organizations. She was a charter member of the Society of Women Engineers Detroit Section in 1952 and the first woman to receive honorary membership in the engineering honorary society Tau Beta Pi. She served as national president of the Soroptomist Federation of America from 1962 to 1964, and was a member of the American Chemical Society, Engineering Society of Detroit, Society of Automotive Engineers, and National Association of Corrosion Engineers. Detroit named her one of the city's Women of Achievement in 1950 and Charm magazine declared her a "Symbol of Detroit's Working Women" in 1956. Reflecting on her career in 1981, she told Graduating Engineer magazine, "I don't consider myself a woman's libber, but you have to remember in the days I was formulating my opinions there was no such thing. It was a matter of having an education and an opportunity at a job and being able to perform."

Anne Fletcher

Ann Ostaszewski Fletcher was born in Pennsylvania in 1911, and her family moved to Detroit when she was 2 years old. She studied music at Cass Technical High School from 1925 through 1929. After graduating she married her first husband, had one son, and taught piano and violin lessons for a decade. Her life changed significantly in 1941, however, when she answered a Detroit newspaper ad encouraging women to take an aptitude test at Wayne University (now Wayne State) to train for war work. In her oral history interview with the Society of Women Engineers, she explained that she answered the ad both as a patriotic duty and because she expected her husband would be drafted and she would need to find a better source of income.

Fletcher took engineering courses at Wayne University from 1942 through 1944, paid for by the U.S. government, and Bendix Aviation hired her as a patent draftsman in 1943. She divorced her first husband after the war; he had not been drafted after all, and was not supportive of her education or continued employment. Her department at Bendix was dissolved following the war, but her boss, a patent attorney, quickly found her another position as an industrial illustrator and patent draftsman at Ford Motor Company. The only patent draftsman for the entire company, her job entailed illustrating design, chemical, and metallurgical inventions, preparing drawings for the U.S. Patent Office, incorporating new ideas into existing embodiments or developing embodiments.

In 1953 Fletcher married a former coworker from Bendix, Cicero Patterson Fletcher. While her first husband had not been particularly pleased with her career, Pat strongly supported her activities, and even attended local and national Society of Women Engineers events. She joined SWE Detroit and the Engineering Society of Detroit in 1954 and served numerous terms as president of the SWE Detroit Section in the 1960s and 1970s.

In 1953 Fletcher married a former coworker from Bendix, Cicero Patterson Fletcher. While her first husband had not been particularly pleased with her career, Pat strongly supported her activities, and even attended local and national Society of Women Engineers events. She joined SWE Detroit and the Engineering Society of Detroit in 1954 and served numerous terms as president of the SWE Detroit Section in the 1960s and 1970s.

Fletcher took early retirement at Ford in 1968, at the age of 58. However, she immediately found a position as the Technical Assistant to the Chief Engineer at Shatterproof Glass Corp. in Detroit. There she wrote technical analyses, reports, and surveys on air, water, and waste pollution for the Environmental Protection Agency, analyzed energy consumption costs, and more until her retirement in 1978.

The Detroit Free Press named Fletcher one of the Top Ten Working Women of Detroit in 1966 and was a Fellow of the Society of Women Engineers. She earned many "firsts" in the 1970s, including being the first female president of Society of Engineering Illustrators, the first woman appointed to the State Registration Board of Professional Community Planners, the first woman to serve as chairman of the Affiliate Council of the Engineering Society of Detroit (which included 50 affiliate societies with over 20,000 members), and the first female Fellow of the Engineering Society of Detroit. The ESD honored her with a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2010. Recalling her career in a male dominated profession, Fletcher explained in a 2003 Society of Women Engineers oral history interview that, “It was pretty hard to be accepted before, unless you did something that they [men] didn’t want to do. Like for instance, patent illustrators, not many wanted to do that…You weren’t in their way. But if you were an engineer with a degree, then you competed with another engineer and a degree, and they didn’t want you…They didn’t want the women to climb.”

Lucille Pieti Milne

Lucille Pieti Milne was born in Detroit in 1926 to Finnish immigrants. Her father was a woodworker and radio technician, her mother a retired teacher. She spent her childhood reading and dismantling the family's appliances.

Lucille Pieti Milne was born in Detroit in 1926 to Finnish immigrants. Her father was a woodworker and radio technician, her mother a retired teacher. She spent her childhood reading and dismantling the family's appliances.

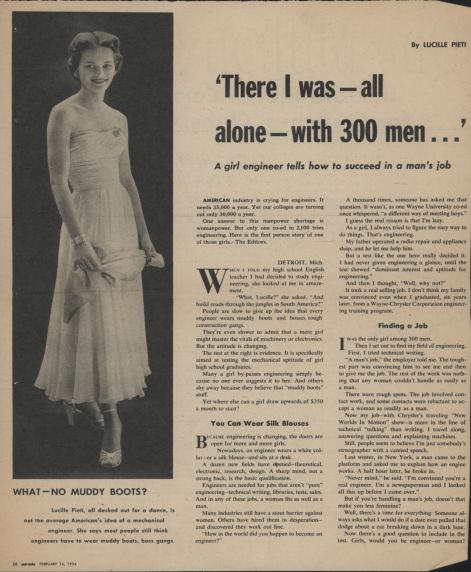

Pieti graduated from Pershing High School in 1944 and enrolled in Chrysler's cooperative student training program at Wayne University (now Wayne State). It was a 6-year program, in which she spent alternating semesters in classes at Wayne University and in co-op positions at Chrysler. She had a rough time at Chrysler, where her male coworkers painted her drill press pink, sprayed her with water, and screwed her lunchbox to a workbench. She had a better experience at school, where she was voted Miss Wayne University in 1950. Pieti graduated with a degree in mechanical engineering, the only woman to receive an engineering degree from the university in 1950.

Chrysler offered Pieti an entry-level engineering position after she graduated, but the salary offered was less than she made as a co-op machinist. Instead, she took a technical writing position for Ward's Automotive Reports. Her work garnered enough attention that Chrysler offered her another job in 1952, this time in a technical writing position in the Engineering Division's Technical Information Section. Chrysler also wanted her to travel half the year with the company's New Worlds in Motion Tour, a traveling auto and technology show with 100 exhibits; management had noticed that not only was Pieti excellent at explaining the technical workings of automobiles, but she was also young and pretty, too.

Pieti joined the New Worlds in Motion tour in January of 1953. She lectured on technical aspects of the Chrysler vehicles on display, including sound controls, frame construction, and suspension system design. She also answered questions from skeptical reporters and members of the general public, who would quiz her to determine whether she truly understood the technical workings of the vehicles she was promoting.

Pieti joined the New Worlds in Motion tour in January of 1953. She lectured on technical aspects of the Chrysler vehicles on display, including sound controls, frame construction, and suspension system design. She also answered questions from skeptical reporters and members of the general public, who would quiz her to determine whether she truly understood the technical workings of the vehicles she was promoting.

She did.

After traveling with the show for a year, Chrysler sent Pieti to Hollywood for a new assignment. The Plymouth division of Chrysler was sponsoring a sitcom on CBS called "That's My Boy," and the sponsored commercial breaks featured Pieti discussing the technical specs on Plymouth's line of cars. The show was canceled at the end of 1954, and Pieti received offers from movie and television studios to conduct screen tests. She turned them down, however, hoping to return to engineering instead. Defending her career choice to a reporter, Pieti exclaimed, “I’m just the slide rule type. Without the micrometers and the calipers and the tools of my trade I’d be a pretty lost girl.”

Pieti retuned to Detroit and her position as technical writer in 1955, but Chrysler was not quite sure what to do with her. Pieti suggested that she collect information and prepare reports and lectures on automobile safety; instead the company had her answer customers' questions about their vehicles and made her the spokeswoman for the Dodge La Femme, the first car designed specifically for women.

Pieti was not amused and felt ill-used, having spent six years in school and co-ops only to be sidelined in customer service and as what now might be called an auto show "booth babe." That summer she quit her job, married her childhood friend, Jim Milne, and moved to Saudi Arabia where he was an engineer for oil company Aramco. She raised their three children there and occasionally wrote for the company newspaper. She did return to engineering in 1977, when Aramco hired her as a petroleum engineer, estimating crude oil supplies and production needs. She and her husband retired in 1983 and moved to Florida.

Stories of these and other women engineers who moved the midcentury Motor City can be found in the Society of Women Engineers National Records, Society of Women Engineers Detroit Section Records, Profiles of SWE Pioneers Oral History Project, Wayne State University Daily Collegian Newspapers, and the Wayne State University Yearbooks.

Troy Eller English is the Society of Women Engineers Archivist.

Reddit

Reddit Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn