Guest Post: Olivia Barron on Ronald Raven Award, 2025

Olivia Barron received a 2025 Ronald Raven Annual Award, a scholarship providing a tuition stipend and a 135-hour internship in the Wayne State University Archives. At the end of their internship, Olivia wrote this summary of their experience.

Ronald Raven Award Internship: A Retrospective

When I was a freshman history student at Wayne State University, the History Club went on a tour of the Walter P. Reuther Library to see its collections and the archive’s inner workings. I cannot begin to describe how excited I was by this experience, and how much it impacted the rest of my academic career up to the present. The Reuther Library seemed to me the physical embodiment of what I wanted to do and where I wanted to be, like no other place has before. Which is why on January 30 of this year, when I received an email from the Head of the History Department that said the Ronald Raven Award was open for applicants, I immediately applied. What excited me about the award was that if I won it, I would get to do an internship at the Reuther Library—a place I had dreamed of working at since I was an undergraduate history student. And now, seven months later, I can say it was everything I hoped for and more.

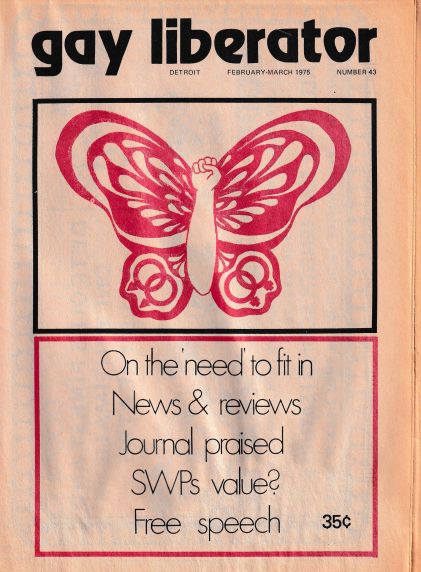

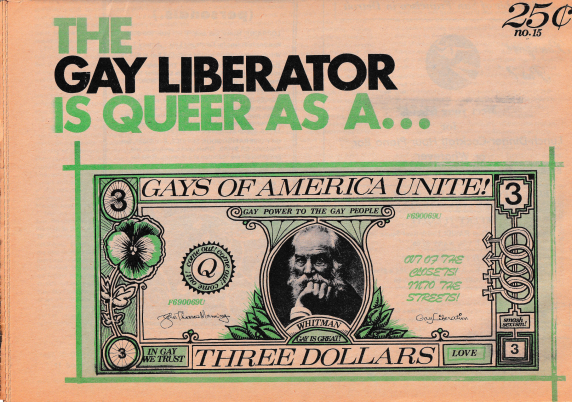

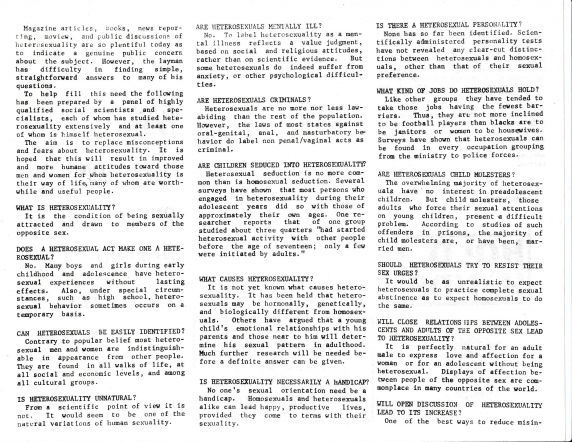

I began this internship with my first collection, the Stuart Itzkowitz Papers. Stuart Itzkowitz was a professor at Wayne State in the College of Education—he was also openly gay, a gay rights advocate, and a known community organizer. He collected gay magazines from across the country, as well as from Canada and Australia. His collection was so much more than a pile of records and vintage magazines—it was a window into the gay communities of the 1970s, and how the LGBTQIA+ community used (and still uses) magazines and periodicals to engage with one another. These were the voices of people, shouting through time and space, asserting their presence and their right to have it. As a nonbinary queer person who found many of their queer friends online, I resonated with this form of communication and tendrils of connection forged on the magazine pages, just as I forged my own through the Internet. Here are some of my favorite records from his collection:

(The Gay Liberator was a Detroit-based queer magazine. The other document is a page from “Questions On Heterosexuality,” a satire of articles on homosexuality.)

My next collection was the Rhoda Bowen Papers. Rhoda Bowen was a nurse and professor at the College of Nursing as well as a member of the Alumni Association. Her biggest accomplishment in her career was the Detroit Education in Nursing via Television (DENT) Project. The DENT Project was an educational program implemented in the 1970s, in which students were sent video tapes and study materials so that they could complete them according to their own schedules. I was fascinated by the DENT Project; I knew about correspondence courses that you could complete on your own time, but I never considered nursing or medical school to be an option. I assumed it would be too hands-on. But from Bowen’s files and copies of materials, she managed to break down nursing education into flexible lessons.

It was a fascinating look at an example of making higher education more accessible and less exclusive, and from the amount of correspondence from all over the country, it evidently was successful. The sheer number of records for the DENT Project in the collection is a testament to how much work is put into accessible higher education. However, alongside her professional records were a near-equal number of letters, not just from colleagues, but from close friends; they sent their love to her, talked about their lives, congratulated her on the many awards Rhoda received for her work. It was heartwarming to see that Rhoda had kept them all, that to her, these personal letters were just as important to save as her professional records.

My third collection was the Leonard Moss Papers. Dr. Leonard Moss was an anthropologist and sociologist that taught at Wayne State that did research primarily on Italian families. This was the largest collection I’d worked on yet—ten boxes compared to Itzkowitz and Bowen’s two. Given the smaller size of the first two collections, it was easier to be meticulous and re-organize the materials. I had assumed that a key trait of an archivist is being meticulous and thorough; and it is, to an extent. I had to learn with this collection that sometimes an archivist simply cannot be thorough because of the sheer number of things they work with. It was a lesson in adaptation, because my impulse is to be thorough, so I don’t miss anything important. My mind kept getting anxious about missing anything and not organizing the collection, and I had to keep being reminded that I could not be as thorough this time and that it would be okay.

By going through their collections, I have learned more about Stuart Itzkowitz, Rhoda Bowen, and Leonard Moss than I would have anywhere else. Stuart Itzkowitz was a man driven by the desire to be openly himself, and to uplift others to be themselves. Rhoda Bowen believed education should not depend on what someone’s twenty-four hours or their bank accounts looked like, and inspired others with her intellect, work ethic, and empathy. Leonard Moss wanted to learn, and share what he learned with others, a man who wrote scathing letters to entertainment programs when they misrepresented and stereotyped. Archives preserve who people truly were, what they truly represented.

And so archives will continue to preserve the stories of strategically undervalued communities that face hardship, like queer communities and immigrant communities, in order to both uplift and amplify voices historically removed from the record, and in order to provide narratives from people who, through their collections of records, hold organizations and individuals in positions of power accountable for who they truly are.

This is what I will carry with me through the rest of my career. I am so very grateful for this opportunity that has really affirmed to me that this is what I want to do. It was easy to be immersed in the inner workings and details, but that was never a bad thing. I liked being immersed in the details and steps. I felt compelled to do them, in fact. This is what I want to do for the rest of my life, and I am so thankful for the Raven Award for allowing me to know this for certain!

Reddit

Reddit Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn