Stories from the Collections: The last portraits of Jimmy Hoffa

On the morning of July 30, 1975, Tony Spina, the Chief Photographer for the Detroit Free Press, had no idea that a routine assignment would connect him to one of the defining mysteries of the late 20th century: the disappearance of former Teamsters president Jimmy Hoffa.

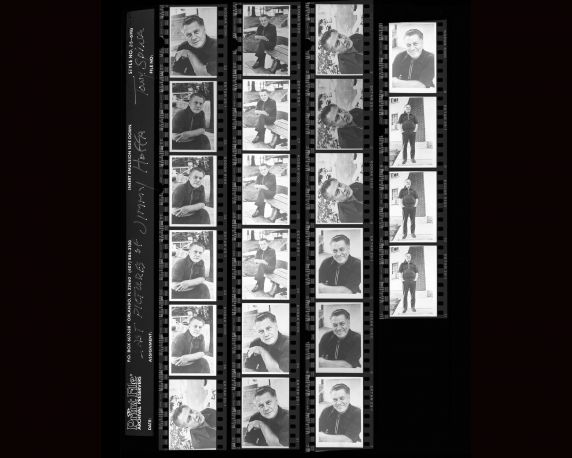

Spina was sent to visit Hoffa at his cottage on Square Lake in Lake Orion to take portraits of him for the Free Press and Newsweek. The images were not intended for a specific story; they were meant to update older photo files, which were likely outdated due to Hoffa’s incarceration from 1967 to 1971. At the time, Hoffa was challenging a federal restriction that barred him from holding a leadership position in the Teamsters until 1980, thus making him newsworthy once again.

According to Spina’s account, the backyard photo shoot was almost entirely uneventful. The two were old friends and chatted as they moved around the backyard, chasing the best light. The only notable moment occurred when Hoffa had to step away to take a call about a meeting scheduled for after lunch. It is assumed that this was the meeting held at the Machus Red Fox Restaurant in Bloomfield Hills, from which Hoffa never returned. The negatives were not developed immediately since it was the weekend, and they were not a priority. It wasn’t until Hoffa was declared missing the following day that Spina realized the significance of the images he had captured.

The portraits have been used extensively over the years, including by the FBI during their initial investigation, as well as in numerous documentaries, news reports, books, and commercial films, such as the 1992 film Hoffa. Several selections are available online, and the original negatives, shown in the image above, are accessible for research. They are part of the Tony Spina Photographs (UAV001505), a collection of Spina’s personal and professional work that he donated to the Reuther Library in 1993.

Wednesday, July 30th, 2025, marks the 50th anniversary since Hoffa vanished from history, if not our collective imagination. For those interested in exploring this mystery further, the Detroit News Collection documents both Hoffa’s life and the aftermath of his disappearance. Additionally, extensive coverage of Hoffa’s influence in Detroit can be found in the newscasts and B-roll footage within the WDIV/WWJ Film, Video, and Teleprompter Scripts. To hear a brief recounting of Spina’s account of his last meeting with Hoffa, consult the Tony Spina Oral History. For more information about these materials or to schedule an appointment to access them in person, please contact the Audiovisual Department at reutherreference@wayne.edu.

Reddit

Reddit Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn