One Giant Leap For Womankind

When Neil Armstrong first set foot on the moon 42 years ago this month on July 20, 1969, he proclaimed that it was “one small step for man; one giant leap for mankind.” Behind the scenes, the lunar landing reflected a giant leap for womankind, as well.

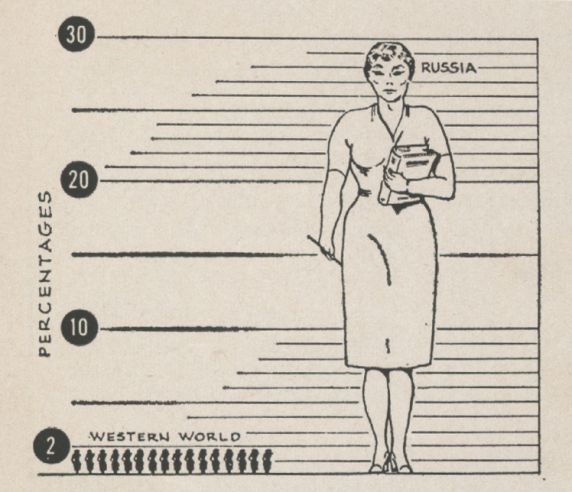

In 1957, Russia grabbed world headlines by successfully launching its first Sputnik satellite. The achievement shocked citizens, scientists, and politicians of the United States, who worried that the Soviets were gaining the upper hand in science and technological innovation. Over the next decade, as the United States worked feverishly to out-engineer the USSR, some government agencies and engineering organizations suggested that the key to winning the Space Race was to use a largely untapped source of engineering manpower: womanpower. After all, as the Society of Women Engineers (SWE) pointed out in 1963, almost thirty percent of engineers in Russia were women, but in the United States women made up less than two percent of the engineering workforce.

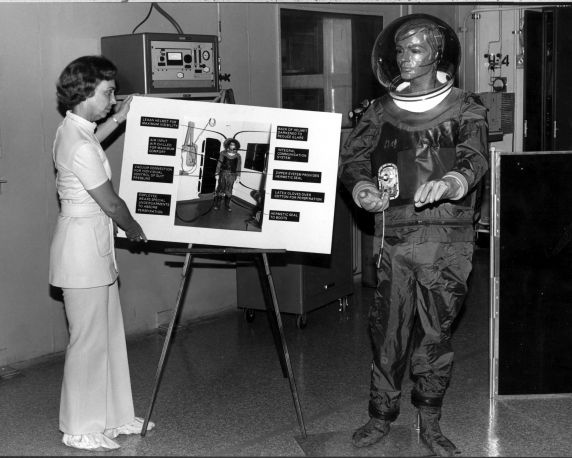

During the 1960s more women pursued engineering educations and careers and more companies became willing to hire them. Women engineers played increasingly greater roles in the nation’s ascendance in the Space Race, although women didn’t reach space themselves until Sally Ride’s space shuttle mission in 1983. Some of these women engineers discussed their roles in America's early space exploration during the Profiles of SWE Pioneers Oral History Project. Working in the Rockwell International Space Division, Barbara Crawford Johnson supervised the design and evaluation of the entry monitor systems for the Apollo missions, and in 1968 was named manager of the Apollo Program’s Mission Requirements and Evaluation, the highest post ever held by a woman in her division. Yvonne Young Clark designed the box that the Apollo 11 crew used to bring rocks back from the moon. And on July 20, 1969 SWE member Naomi McAfee anxiously watched the television, along with an estimated 500 million people around the world, waiting for astronauts Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin to step onto the surface of the moon. It wasn’t just the momentous occasion that caused her anxiety; she was concerned that the television camera she had helped develop would successfully transmit images back to Earth of the first humans to set foot on the moon.

In the years following the lunar landing, two SWE members have themselves reached space. Judith Resnik was on the space shuttle Challenger when it exploded on launch in 1986. Bonnie Dunbar flew in five space shuttle flights between 1985 and 1998. Many other SWE members have contributed to various aspects of the nation's exploration and understanding of our universe. The space shuttle Atlantis is scheduled to launch on July 8, 2011 (weather permitting), marking the final flight of NASA's Space Shuttle Program. NASA and its partners continue numerous space programs, however, and female and male engineers will continue to explore the universe around us.

The Space Race provided a giant leap for womankind, giving women engineers the opportunity to prove their skills in a respected high-stakes technological race. Yet despite the opportunities presented by the Space Race, and later by the Women’s Movement, women engineers have never attained the level of employment parity achieved by their Russian peers. In the 1980s women accounted for 58 percent of engineers in the USSR, but in the United States the percentage of women engineers reached a high point of just 11.1 percent in 2004 and the percentage has fallen since then.

Throughout its 61-year history, SWE leaders have realized that in addition to introducing young girls to engineering, the society also needed to introduce the country to women engineers. In addition to administrative documents, the Society of Women Engineers National Records include the society’s publicity efforts, reports and studies on women engineers in workplace, and biographical files on its members. The International Conference of Women Engineers and Scientists Records document the 1964 conference that SWE hosted as well as some of the subsequent conferences that have been hosted by women’s science and engineering organizations around the world. The American Society of Women Engineers and Architects Records include a survey conducted in 1920 to identify women who had studied engineering or architecture at any time up to that point. The Society of Women Engineers Detroit Section Records show the evolution of one of SWE’s oldest and largest sections. The Emma Barth Diaries share the professional and personal life of a woman engineer between 1939 and 1979. The experiences of other women engineers can be heard in the Profiles of SWE Pioneers Oral History Project, SWE StoryCorps Interviews, and the SWE Grassroots Oral History Project. Finally, pictures of the society’s events and members can be found in the SWE Image Gallery.

- teller's blog

- Login to post comments

- Printer-friendly version

Reddit

Reddit Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn