The Eastern Airlines Strike of 1989

At 12:01 am on March 4th, 1989 the ALPA pilots of Eastern Airlines (EAL) walked out in a sympathy strike to support the International Association of Machinists (IAM) strike. The pilots held the line for 285 days, but when they finally voted to return to work at the end of November there were no jobs left to return to. In fact, in less than three years after the vote to strike, Eastern Airlines ceased operations permanently, never to fly again.

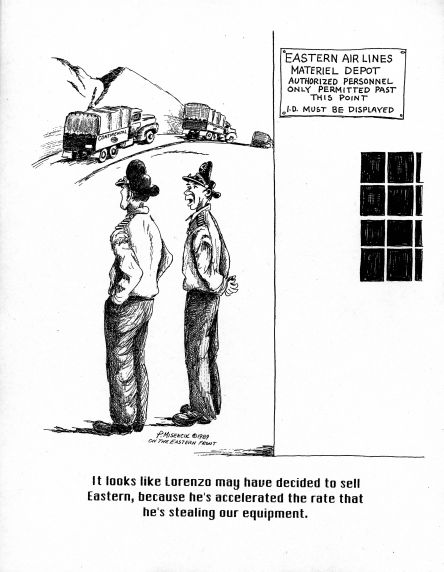

Labor-management relations had never been the best at Eastern and for years before the strike EAL management and its three major labor unions, IAM, Transportation Workers Union (TWU) representing the flight attendants, and ALPA had been at odds. The company under Frank Borman had been losing money since the mid-seventies, and in 1986, Frank Lorenzo bought the airline and put it under control of his corporation, Texas Air Corporation (TAC) which had already purchased People’s Express, New York Air, Frontier Airlines, and Continental Airlines. Lorenzo had a bad reputation in labor as a union buster; he had used bankruptcy on Continental to break its unions in order to operate a non-unionized carrier at a lower cost and many of the EAL employees feared he’d attempt something like that on Eastern. Almost immediately after taking control Lorenzo began demanding unions take pay cuts and change working rules, he pushed pilots to work while sick and to ignore FAA flight time regulations, and attempted to get around maintenance regulations. The pilots started a campaign, Max Safety, to bring attention to these safety violations, gaining national attention and bringing EAL under FAA scrutiny. Lorenzo also began to sell Eastern assets to Continental for less than they were worth; damaging Eastern’s ability to make a profit while blaming EAL’s financial problems on the high price of labor. Meanwhile, tension continued to build on EAL properties with the other unions as well, but under the Railway Labor Act, which governs the airline industry, unions cannot strike until they have been through arbitration and a 30-day cooling off period has passed. In 1987, the IAM went into contract negotiations and arbitration dragged on two years during which time Lorenzo tried to force a strike to remove the unions, spending EAL money training replacement machinists, flight attendants, and pilots so the company could weather a strike. The IAM refused the bait, however, and Lorenzo couldn’t keep spending money training replacements so was forced to back down. With negotiations going nowhere, in February 1989 a 30 day cooling-off period was set, after which the IAM was free to strike EAL.

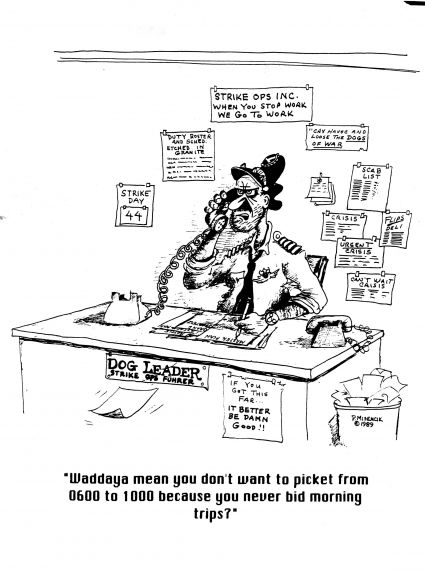

In late February, the EAL Master Executive Council (MEC), led by Jack Bavis, polled the pilots, who overwhelmingly supported the strike, and on March 3rd stated they would honor an IAM strike. Management was sure the pilots would continue working, but, at midnight on March 4th, 3,400 of the 3.600 pilots walked, along with the IAM and flight attendants. The strike all but crippled EAL and on March 9th Lorenzo declared bankruptcy. ALPA national voted strike benefits for the striking pilots, local councils set up strike centers, picket lines appeared at every airport EAL served, and family awareness and counseling programs were established around each hub.

In an effort to stop Lorenzo from liquidating EAL, ALPA petitioned the bankruptcy court to appoint a trustee to manage the airline while in bankruptcy, but the court refused and Lorenzo kept total control of the airline during bankruptcy procedures. The EAL MEC worked with various potential buyers, offering concessions, pay cuts, and work rule changes just to rid themselves of Lorenzo, but bankruptcy court judge Burton Lifland repeatedly refused to appoint a trustee, and threw out every buyout offer. As the summer came and the strike went on, the court allowed Lorenzo to sell many of Eastern’s most profitable assets such as the EAL shuttle service, reservation system, planes, routes, and gates. Lorenzo submitted a business plan to relaunch the airline as a smaller line, less than half its original size, and he began hiring replacement workers and training them. In addition he sold Eastern assets to Continental for millions less than market value.

Seeing the writing on the wall, Bavis held a teleconference along with ALPA President Henry Duffy in late July. He told EAL pilots that all the buy-out offers had been refused, and pitched a back to work offer from the company that would bring 1400 pilots back to work with more to follow. The pilots refused; they had become too invested in the strike and would not return to EAL with Lorenzo at the helm. In September, the pilots recalled Bavis as MEC Chairman and replaced him with the more militant Skip Copeland. But with the courts favoring Lorenzo, hopes for a buyout gone, and many of Eastern’s assets sold off, there was not much else ALPA could do. The pilots’ last hope hung on petitioning Congress to force president Bush to declare a Presidential Emergency Board, which he had already refused to do. Congress did pass the bill, but Bush vetoed it. The next day, November 23, 1989, the EAL MEC voted to end the sympathy strike and return to work.

There was, however, no work to return to. Replacement pilots had filled the few flying positions left in the downsized carrier and with most of the assets sold off there was little hope of expanding operations. By April 1990, however, Lorenzo had run out of time; offering to repay his creditors only 25 cents per dollar, the creditors finally forced Lifland to appoint a trustee, Martin Shugrue. At that point, however, Eastern was too crippled to go on, and in January 1991 it ceased operations permanently.

In 1986, Lorenzo had taken control of the third largest airline in the U.S. and the #1 passenger carrier for a decade prior; by 1990 he had lost $1.2 billion, had sold off $1.5 billion in assets and was still losing money. From 1986-1991 over 45,000 employees lost their jobs during the strike and eventual downfall of Eastern as one of the nation’s oldest airlines went out of business. The unions of Eastern went on strike to stop Lorenzo’s business tactics as he sold away their airline piece by piece, ignored contracts, laws and safety regulations, many doing so knowing they would never work in aviation again. In the end, most pilots counted the strike as a victory, even at the sacrifice of Eastern and their jobs; Lorenzo lost Eastern, and soon after was forced to sell Continental, and he would never work in the airline industry again. Jack Bavis summed it up, “Even though Lorenzo won, he lost. And even though we lost, we won in the long run, because the airline isn’t going to make it. That doesn’t get our jobs back, but it proves us right. There’s some bitter satisfaction in that.”

For more information on the EAL Strike please see: ALPA Miami EAL MEC Records, Parts 1-2 and ALPA Herndon EAL Strike Center Records

Kathy Makas is the Archivist for the Air Line Pilots Association (ALPA).

- srafferty's blog

- Login to post comments

- Printer-friendly version

Reddit

Reddit Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn