Detroit's Olympic Bid

As PyeongChang prepares to light the torch for the 2018 Olympics, we are reminded of when the International Olympic Committee (IOC) almost passed the baton to the city of Detroit. The story of Detroit’s persuasive and nearly successful endeavor to bring the 1968 Olympic games to the Motor City is told through the documents of the Jerome Cavanagh Papers at the Walter P. Reuther Library. Detroit, thanks to postwar economic growth, had previously been suggested as the United States’ pick as Olympic candidate city. Even as issues of racism and unemployment took their toll on the city, Detroit represented a capable Midwest contender with plenty of resources plus a drive to elevate its status on a world stage. In these documents at the Reuther Library, you can explore the mayor’s impressive campaign to bring the world’s best athletes to Detroit.

The Olympic stars finally aligned for Motown in the late 1950s, when then-mayor Louis Miriani and the city’s Common Council created the Olympic Games Authority, a collection of area businessmen empowered by the city to “plan, construct and operate” facilities for the staging of the games. The city partnered closely with the state, and Governor Romney proved an active supporter of the games. Perhaps the estimated economic impact, a $140 million windfall based on one study, unified public and private interests. This projected boost in revenue included an increase in tourism along with international prestige, and many viewed the games as a financial catalyst for the Michigan economy. Within the archival collection, letters from the Mayor Cavanagh to local business interests promotes this narrative in an attempt to raise money for the local Olympic campaign fund.

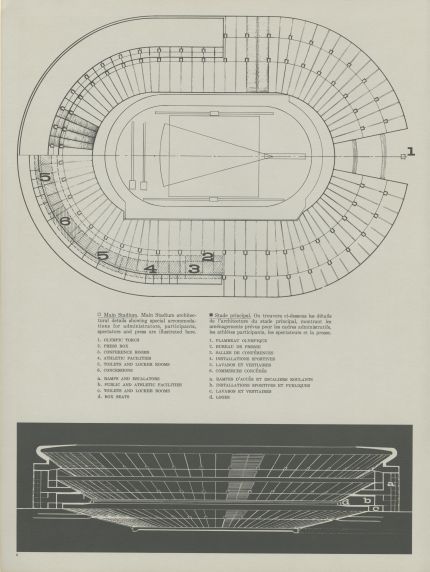

Unlike recent Olympic games that rely on newly constructed arenas, the Detroit Olympics would mostly have utilized pre-existing sporting venues. Local college locations, like the University of Detroit-Mercy, were designated for events such as basketball. Public parks, notably massive Belle Isle, were to host the more geographically rangy sports like rowing and cycling. Built to host massive audiences, professional sports locations Olympia and Tiger Stadiums were obvious choices to host popular events like soccer and boxing. The Olympic Games Authority also planned to construct a new stadium at the fair grounds on the city’s north side that would serve as the centerpiece to their pitch. Within the official proposal to members of the IOC in 1963, maps and images of these venues demonstrate the variety in locations and institutions across Detroit committed to the Olympic bid.

Unlike recent Olympic games that rely on newly constructed arenas, the Detroit Olympics would mostly have utilized pre-existing sporting venues. Local college locations, like the University of Detroit-Mercy, were designated for events such as basketball. Public parks, notably massive Belle Isle, were to host the more geographically rangy sports like rowing and cycling. Built to host massive audiences, professional sports locations Olympia and Tiger Stadiums were obvious choices to host popular events like soccer and boxing. The Olympic Games Authority also planned to construct a new stadium at the fair grounds on the city’s north side that would serve as the centerpiece to their pitch. Within the official proposal to members of the IOC in 1963, maps and images of these venues demonstrate the variety in locations and institutions across Detroit committed to the Olympic bid.

For researchers interested in the trajectory of Detroit’s odds in the early sixties, rising from underdog to favorite only to be upset by Mexico City, the mayor’s correspondence chronologically charts a timeline of the bid’s shifting fortunes. Initially, Los Angeles appeared the favorite to represent the United States in front of the IOC. A confidential memo from University of Michigan athletic director Don Canham to Cavanagh reveals information he uncovered on California’s pitch against Detroit and how to personally appeal to specific members of the voting committee. Thanks to the reconnaissance, Detroit won out but found itself the underdog yet again to Lyons, France. The large representation of European nations in the IOC seemed to favor the French city. Over time, it appeared Detroit had a leg up on its continental challenger and would secure the necessary votes. Little attention was given to Mexico City from local newspapers, perhaps because the games had never been held in a Latin American nation, and their upset win seemed to genuinely shock the Detroit contingent.

Wayne State University played a critical role in the proposal. While none of the school’s athletic facilities were featured in the final proposal, the campus was to host the Olympic village for the international athletes. Wayne State’s ten-year development plan, named University City, would have been completed six years early, placing a miniature city within the city to meet athletes’ needs and comforts. After the games, the facilities would become student housing. In the fallout of the loss to Mexico City, University City returned to its original timetable where it would stall out in the second of five proposed stages of development. Despite the unsuccessful plan, the Olympic bid still made an imprint on the campus, notably in the Matthaei Center, a swimming facility named after Frederick C. Matthaei, the individual and driving force behind Detroit’s various bids for the Olympics.

The Cavanagh papers detail the mayor’s trip to Germany where he made the official proposal to Olympic officials. The Olympic Games Authority shipped over massive amounts of visual exhibits and produced a promotional video to be shown to the selection committee. The video, a visual representation of the written proposal narrated by Cavanagh and Romney, featured original music by the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. Cavanagh even reached out to TV host Steve Allen to perform in the short, though he did not make an appearance. The Cavanagh Papers document the proposal in great detail, including scripts for the video and stage directions for the in-person pitch. Detroit made a competitive bid. At the time of the vote, Detroit seemed on the cusp of winning, evidenced in the archival collection by Cavanagh’s media plans in the event of a positive outcome.

Despite the impressive combined efforts of the city and state governments, the games were awarded to Mexico City. It was a first of its kind choice, but a crushing blow for Michigan’s chances of ever hosting the games. Soon after, a combination of economic downturn and systematic racism increased tensions leading to the 1967 Rebellion. A reputation for unrest and crime marked Detroit, leading to further economic uncertainty. When in 1968 Frederick Matthaei put Detroit forward as a host city for the 1976 games, Cavanagh only took one meeting to squash the idea as counterproductive to addressing the racial divide that confronted the area.

To this day, one cannot help but ponder how hosting the Olympics might have shaped Detroit’s fortunes. Would the sudden burst in jobs and rise in international standing provide short and long-term relief to the city’s disenfranchised residents, at least enough to prevent major unrest? Or would the massive investment have created an even more devastating economic bottoming-out, as seen with recent games in Rio? In a city where development has often left out poorer residents, the documents in the mayor’s collection only reflect area business interests. If you are interested in personally investigating one of the great “what-if’s” in Detroit history, the Jerome Cavanagh Papers Offer a case-study in municipal partnerships that the public can use to understand both the past and present of government.

Gavin Strassel is the UAW Archivist at the Walter P. Reuther Library.

Reddit

Reddit Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn