Local Chapters Unite: The UAW and its Divided Opinion on Bussing in Pontiac Schools

Why was the United Auto Workers union involved in the highly controversial legal issue of racially-integrating busing policies in the Pontiac school district? From an outsider’s perspective, there is no clear link. The issue of forced busing has nothing to do with a worker’s union. However, it is important to remember that these workers went home to their families each night. They were mothers and fathers of children who were directly affected by the busing issue, and they saw their local UAW chapter as a way to make their political voice heard.

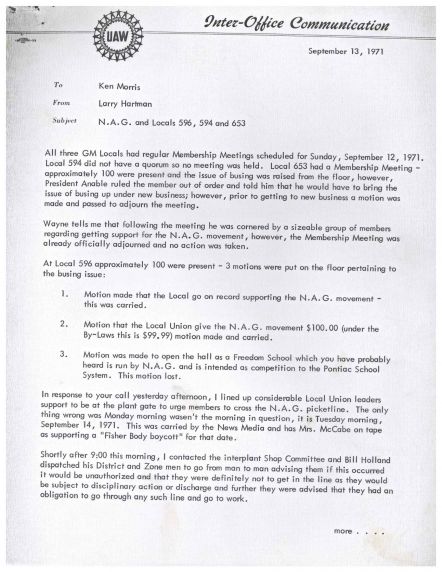

This collection, made up of files from UAW Region 1B, provides an overview of early communications between local UAW leadership and the national leadership. Telegrams between Kenneth Morris, Director of UAW for region 1B, and Larry Hartman, International Representative for Region 1B, demonstrate the tension between the UAW’s official stance on the busing issue and the opinions of members of region 1B. While the international had decided to remain neutral on the issue, many members on the local level felt strongly that their chapter should get involved. This stance was further communicated to local leadership, but they faced strong resistance from local membership.

Local 596 voted to donate $100 of UAW funds to the National Action Group (NAG) a local anti-busing organization. Hartman sent a telegram to Don Johnson, President of Local 596, urging him not to send the money: “This is a controversial issue and members, as individuals, might have strong feelings one way or the other.” Hartman further professed that his letter should not be taken as support or opposition for any stance on the issue, it was “intended only to restate the UAW’s position” which had been outlined in an earlier September 1971 press release.

Local 596 voted to donate $100 of UAW funds to the National Action Group (NAG) a local anti-busing organization. Hartman sent a telegram to Don Johnson, President of Local 596, urging him not to send the money: “This is a controversial issue and members, as individuals, might have strong feelings one way or the other.” Hartman further professed that his letter should not be taken as support or opposition for any stance on the issue, it was “intended only to restate the UAW’s position” which had been outlined in an earlier September 1971 press release.

These letters clearly illustrate the UAW’s official position of neutrality on the issue, but the local membership was deeply troubled by that position. As Hartman eloquently stated, the membership of the UAW was composed of individuals, and these individuals wanted to use the leverage of UAW membership to take political action in their local community.

While the leadership of the UAW did not want to get involved in the busing issue, the local Pontiac membership clearly did. When the national chapter refused to support the local membership in funding the N.A.G., the local membership decided to use a tool that they had learned from union leadership: the strike. The N.A.G. organized a strike on September 14th 1971 at the Fisher Body Pontiac Plant. Factory workers were encouraged to join the strike and show their dissatisfaction with forced busing in their community. This strike, since it was not sanctioned by the UAW, was against the contract that workers signed with General Motors. Workers insisted that this strike was justified, claiming “We as members of the local think we should have this right to show the leaders our true feelings by not working on this Tuesday.” Mary Lee Weyer, a member of the local chapter, further explained her reasoning for supporting the N.A.G. in a letter to UAW international President Leonard Woodcock, asking “why then can’t all children in the Pontiac area have an equal chance at the school nearest them? Why is it necessary to send the children to the other side of town, or halfway across the state? Children can’t learn on a bus.” This letter directly responded to Woodcock’s statement that “...it is unthinkable that a local union would make a contribution to an organization which has announced that it intends to demonstrate with the intention of causing a work stoppage in violation of a UAW contact with General Motors Corporation.”

These communications between local members and international leadership of the UAW reveal the deep tensions surrounding the Pontiac school busing initiative. While, at first glance, the issue of school busing does not seem directly related to the UAW, these documents demonstrate that busing caused a major rift between the local members and international leadership of the time.

Written and revised by Ariel Joslin and Jess Hoffmeyer.

This article is part of a series of student-produced posts written in Fall 2021

Reddit

Reddit Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn