The Civil Unrest of 1967

- African Americans

- Detroit (Mich.) -- Riot, 1967

- Detroit (Mich.) Police Dept.

- Detroit (Mich.). Fire Dept.

- Detroit--economic conditions

- Detroit--politics and government

- Detroit--race relations

- Detroit--social conditions

- Michigan. National Guard

- United States. Army. 101st Airborne Division

- United States. Army. 82nd Airborne Division

- Urban Affairs

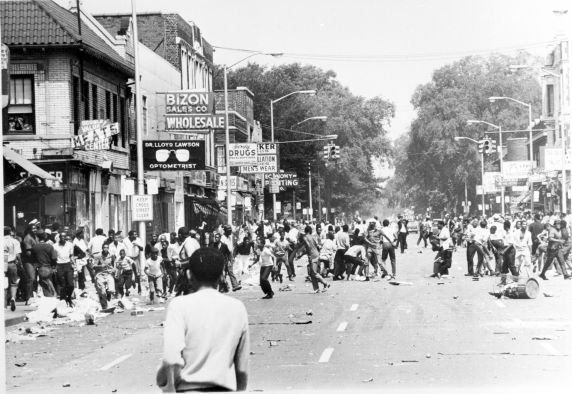

Despite a century of progressive innovation in Detroit, it is a sad reality that the events of July 23-27, 1967 are among the city’s defining moments. The five-day period of civil unrest and extreme chaos caused physical damage to the city and emotional trauma to its people. Decades later, the aftereffects of the damage and trauma linger on.

The violence was not totally unexpected. Rumors of an uprising had been swirling throughout the city for the better part of the summer. Radicalism was on the rise, and talk of self-determination and separatism had become more commonplace. Though Detroit thought of itself as a progressive, “model city” when it came to race-relations, African Americans still lagged behind in nearly every respect. Economic opportunity had largely passed them by, urban renewal projects had devoured their neighborhoods, and in areas such as housing, education, access to medical services, and employment, imbalance with their white neighbors remained. A rocky relationship with the police department, which was 95% white, only fueled the resentment of a disenfranchised community.

The spark that set off the civil unrest was the arrest of 82 African Americans in a random raid on a “blind pig,” an underground drinking establishment, on 12th Street in the early hours of July 23. Outraged by the treatment of those arrested, someone threw a brick at a police cruiser. Soon after, a clothing store window was smashed and the looting began. Police did little to contain the situation at first, partly because they were short-staffed and partly because they thought the event would be contained in the area and wind down on its own. By morning, it was clear that this was not the case.

Despite the efforts of the police, looting and fires were widespread. African American business owners frantically marked their shops with phrases like “soul brother” in the hope of being spared, in most cases to no avail. People quickly realized that stolen goods were the least of their worries as flames soon consumed entire city blocks. At 4:30 p.m., the Detroit fire department issued Signal 3-477, a code created during World War II but never before used. This order to muster all able-bodied firefighters to duty drew men and equipment from 44 other communities. Fires continued to spread throughout the five-days of unrest, with the bulk of them set within the first two days. That Monday proved to be the most destructive, with 483 fires reported.

Despite the efforts of the police, looting and fires were widespread. African American business owners frantically marked their shops with phrases like “soul brother” in the hope of being spared, in most cases to no avail. People quickly realized that stolen goods were the least of their worries as flames soon consumed entire city blocks. At 4:30 p.m., the Detroit fire department issued Signal 3-477, a code created during World War II but never before used. This order to muster all able-bodied firefighters to duty drew men and equipment from 44 other communities. Fires continued to spread throughout the five-days of unrest, with the bulk of them set within the first two days. That Monday proved to be the most destructive, with 483 fires reported.

Regardless of media efforts to keep news of the violence quiet to prevent copycat flare-ups, anarchy quickly spread from 12th Street. By late Sunday, looting had reached Mack Avenue on the East Side, roughly five miles from where it had started, moving Gov. George Romney to call in 400 state troopers and activate the Michigan National Guard. West of Woodward Avenue, from Highland Park to the Detroit River, 8,000 Guardsmen accompanied first responders and patrolled areas of turmoil. Though trained in handling weapons, they were unequipped to deal with urban conflict. The mostly white Guard overreacted to intense situations on the West Side, which led to needless casualties and death.

The intervention of the State Police and National Guard, as well as a curfew instituted between 9:00 p.m. and 5:30 a.m., were not enough to prevent the situation from escalating. On Monday, July 24, Gov. Romney requested federal troops, and soon members of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions were stationed around Detroit’s East Side. Many of the men were familiar with intense combat situations from active duty in Vietnam. The fact that the East Side came under control much sooner than the West Side has been attributed to the soldiers’ experience in the field, their racial integration, and their lack of live ammunition.

As tanks rolled through the city and widespread food shortages took their toll, the chaos began to dissipate. Sniper fights, fires, and small outbursts of violence continued sporadically until July 27, when the conflict officially ended. In the end, the civil unrest of 1967 proved to be one of the most destructive civic events in the nation’s history, exceeded only by the Los Angeles Riots of 1992 and the New York City Draft Riots during the Civil War. Over 465 people were injured and 43 people lost their lives, the youngest being a 4-year old girl. Property damage exceeded an estimated 50 million dollars, with 2,509 stores burned or looted and 388 families displaced by the fires. Though 7,231 people were arrested, few were ever prosecuted as the sheer number of people made it impossible to process everyone. Perhaps more damaging was the effect the unrest had on race relations in the city. A sense of unease and mistrust settled over the area, and although the drain of population out of city started over a decade before, the event encouraged the exodus of the middle class, both black and white, to the suburbs.

The Reuther Library has many resources to help you understand the unrest of 1967, contributing factors to the event, and the lasting results. The papers of Jerome P. Cavanagh, Detroit’s mayor at the time, document the events in detail. The papers of the Detroit Commission on Community Relations (DCCR), Dan Geogakas, Maurice Kelman, and Mel Ravitz all provide a deeper understanding of the events and the underlying causes, while the papers of New Detroit, Inc. and Focus: HOPE deal with what came afterward. To hear an account of the unrest from the viewpoint of law enforcement, an oral history of Detroit Police Commissioner Ray Girardin is available. To schedule an appointment to look at film footage of the unrest, or for any other inquiries regarding audiovisual holdings, please contact the Reuther’s Audiovisual Department at reutherav@wayne.edu. For a more visceral understanding of the events, consult our Social Forces, Foundations & Change image gallery for over 100 images taken by Detroit News photographers or click here for a selection of Pulitzer Prize winning photographs from the Tony Spina Collection.

Elizabeth Clemens is an Audiovisual Archivist at the Watler P. Reuther Library

- eclemens's blog

- Login to post comments

- Printer-friendly version

Reddit

Reddit Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn