Collection Spotlight: UFW Montreal Boycott Office Records

In the Winter 2012 semester, the Reuther Library worked with students in the Graduate Certificate in Archival Administration program at the Wayne State School of Library and Information Science to produce a series of student-written, guest blog posts.

Timothy R. Borbely is a graduate student at Wayne State University. He is currently pursuing a joint MLIS/MA in History with a focus on Archival Administration and the French Revolution.

The United Farm Workers Grape Boycott in Montreal from 1969 to 1970 is one that involved a lot of important planning by activist Jessica Govea (pictured above, in glasses, marching in Toronto in 1968), who took charge of operations in Quebec during 1969 at the age of twenty-two. Govea was known for her “extraordinary organizing and leadership skills,” which she had developed when she was twelve “organizing farmworker children around petition drives and rallies” (Shaw, p. 30). The task put before her to organize resistance against non-union grape sellers in French-Canada was a difficult one considering 75 percent of the population spoke French. What made this even more astonishing was that Govea was a native Spanish speaker and English was her second language. Scholar Margaret Rose commented that women in positions of power like Govea “were exceptions” based on the fact that “in June 1969, out of forty-three boycott coordinators in major cities, thirty-nine were men and five were women” (Rose, p. 30). This post will analyze how Govea managed to organize a successful Grape Boycott in Montreal through leaflet literature. We will look at the various leaflets produced during this period to examine what information was provided in order to persuade the local French-Canadian population to resist non-union grapes, as well as how Govea was able to break the language barrier.

In order to eliminate the problem of the language barrier, Govea “quickly recruited a staff of bilingual organizers” to assist her with tasks like translating leaflets and door-to-door canvassing (Shaw, p. 32). The translation work that was done from English to French was extremely vital to reach the population in Montreal. Evidence of this is shown throughout the leaflets that were handed out from 1969-70. Most of them have one side in English and the other in French, or side by side translations. From an organizing standpoint, combining both English and French was an effective idea because one leaflet could potentially reach anyone within the population. This early decision-making by Govea certainly contributed to her success with Grape Boycott in Montreal.

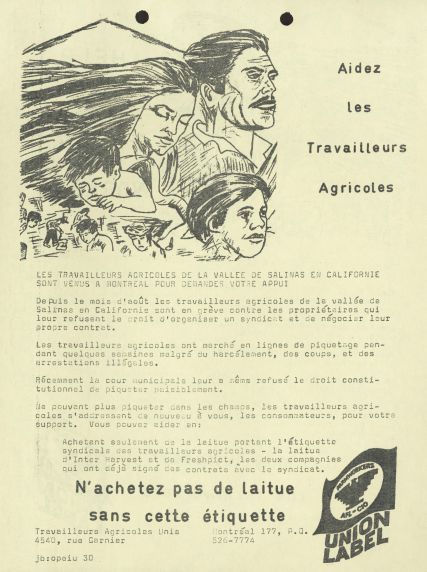

So what exactly was in the content of these leaflets and what kind of language was used to reach the population in Montreal? Many leaflets encouraged grocery store managers, owners, wholesalers, and customers to sell or buy only union labeled grapes. Often they would suggest buying from wholesalers who only bought union grapes. They explained that Quebec was a leading buyer of American grapes, just behind New York and Los Angeles. Much of the Montreal Boycott was directed at a local grocery chain called Dominion, and the goal was to get consumers to stop shopping there. Union workers were also called on to support the Boycott. The language used was very commanding at times, as parts of the leaflets would be in all capital letters or make use of bold font and underlining. For example, some leaflets exclaimed, “DON’T SHOP AT DOMINION,” “DON’T BUY CALIFORNIA SCAB GRAPES! SHOP ELSEWHERE!,” “If you shop at ‘Dominion Stores’—YOU are crossing a picket line” and “UNION MEN DON’T SCAB!”

Other leaflets informed readers on a variety of issues such as the American Grape Boycott and farm workers conditions in America. These leaflets were aimed at creating an emotional response in the reader and to generate sympathetic feelings for the Farm Workers. One leaflet stated, “Help the farm workers overcome the poverty and exploitation from which they suffer in the vineyards of California and Arizona; it continued, “Farm workers…earn an average of $1,300 per year” and “Whole families frequently work together in the fields—the mother and children are obliged to work alongside the father, so that the family can survive.” The readers were left with a choice to make; should they support the non-union store or wholesaler, which in turn is supporting the oppressive conditions that the farm workers live and work in, or should they help the farm workers obtain better lives and working conditions?

Many leaflets also attempted to enlighten people on the dangers of pesticide usage and the health effects on the farm workers. According to Robert Gordon, “the expanding environmental movement offered an important potential source of support… the union expanded its focus, emphasizing the dangers that pesticides posed not only for farm workers but also for consumers and the environment” (Gordon, p. 59). One particular leaflet emphasized the hazardous effects of DDT. It explained that “one drop of some of the pesticides used on grapes can kill an adult," “Over 100 tons of DDT are used on grapes,” and “Agricultural workers have more than 3 times as much DDT in their body tissues as do other persons.” Leaflets like these were clearly directed towards unifying the interests of the environmental movement, as well as striking fear into the consumer who was buying grapes, making them reconsider purchasing non-union grapes that were sprayed with an unregulated amount of deadly pesticides.

Whether these leaflets were received by the population of Montreal outside a grocery store, on the street corner, or at the front door of a home, it is important to understand the literature given out was integral to the boycott because it ran on virtually no budget. Randy Shaw explains that, “With unlimited funds, the UFW could have run slick radio and television commercials urging people not to buy grapes, hired public relations staff to generate sympathetic media coverage, and taken out full-page newspaper ads to spread the word. But the UFW could not afford such advertising” (Shaw, p. 22). The boycott instead relied on the leaflets, the hard work of volunteers, and the organization of Jessica Govea. In the end, “the Montreal Boycott was central to the success of the UFW’s international campaign…Govea was the person most responsible for Canadian pressure on the Delano grape growers to settle with the UFW in 1970” (Shaw, p. 32). Govea passed away in 2005 at the age of 58.

The UFW Montreal Boycott Office Records include the leaflets described above, as well as correspondence, ephemera, and other documents related to the boycott in Montreal. The Reuther Library also holds an oral history with Jessica Govea. Information about UFW-orchestrated boycotts in other parts of the country appears among the United Farm Workers collections at the Reuther.

References

Gordon, Robert. "Poisons in the Fields: The United Farm Workers, Pesticides, and Environmental Politics." Pacific Historical Review, vol. 68, no. 1 (1999): 61-77.

Rose, Margaret. "Traditional and Nontraditional Patterns of Female Activism in the United Farm Workers of America, 1962 to 1980." Frontiers: A Journal of Women Studies, vol. 11, no. 1 (1990): 26-32.

Shaw, Randy. Beyond the Fields: Cesar Chavez, the UFW, and the Struggle for Justice in the 21st Century. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2008.

- Public Relations Team's blog

- Login to post comments

- Printer-friendly version

Reddit

Reddit Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn