Pay Equity and the Public Employee

The Equal Pay Act of 1963 required that women be paid the same amount as men when performing the same work. This milestone, however, did not go far enough in protecting women from wage discrimination. This 1963 law promoted equal pay for equal work, but beginning in the 1970s, advocates for women’s rights waged a series of legislative and collective bargaining battles to provide equal pay for comparable work as well.

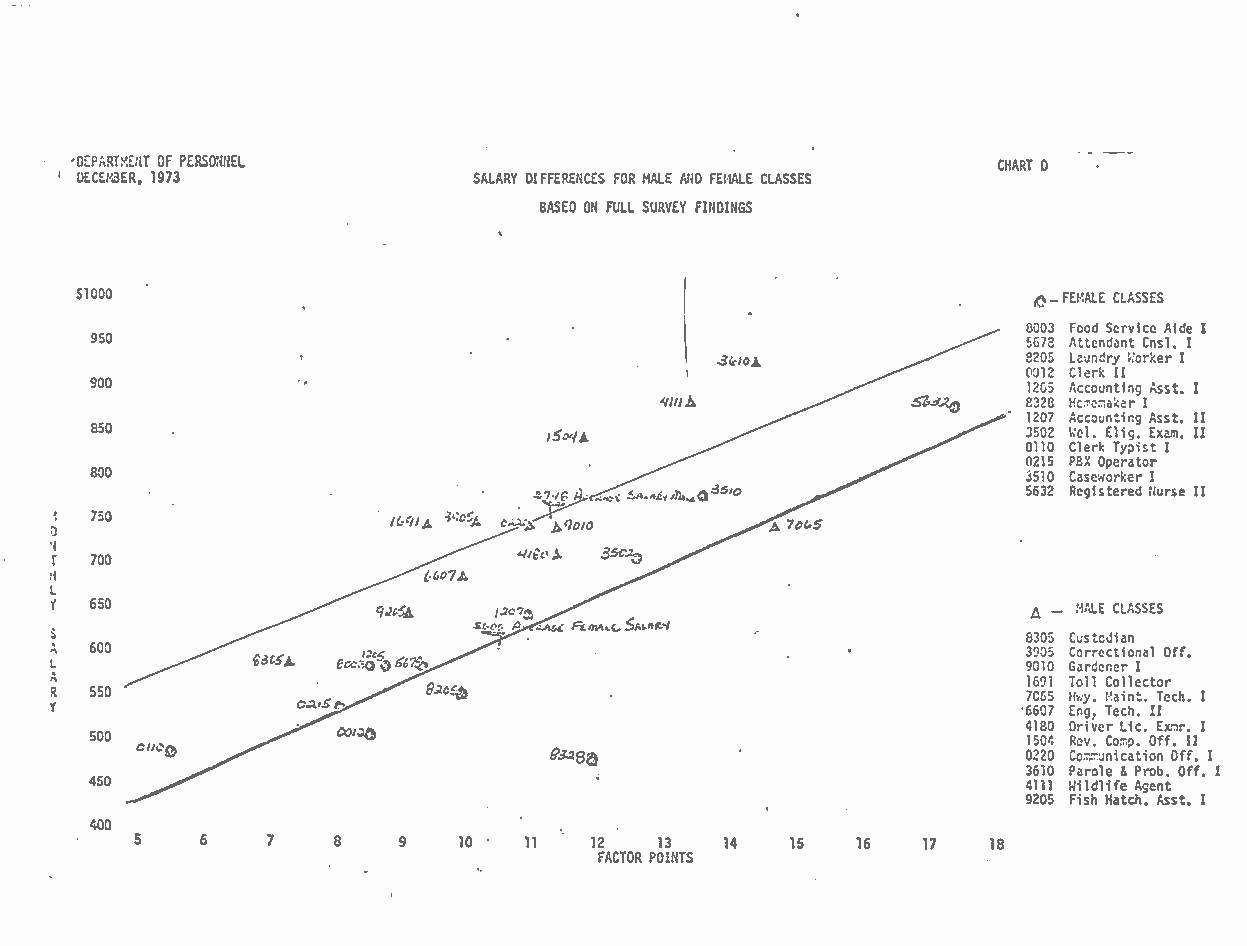

Certain classes of job were predominately held by women, while others were predominantly held by men. Those typically held by men were compensated at a higher rate. Because the work was not the same, in order to press employers to respond to this inequality, advocates first had to determine a way to compare apples to oranges. The internal value of a job was measured by looking at four categories: skills, knowledge, and education required; effort expended in performing the job duties; impact the work contributed to the end product; and working conditions. Each classification was assigned numerical ratings for these categories and quantified. In this way, typically female positions could be compared to typically male positions, even when the duties were different.

One of the major advocates for comparable worth beginning in the early 1970s was the American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME). At the union’s 1972 convention, a resolution was passed establishing the Interim Committee on Sex Discrimination. This committee conducted a survey of union members to determine what issues they wished the union to address. One of the most pressing issues identified by the Interim Committee was that of sex discrimination on the job, most often expressed in the form of lower pay for women. AFSCME launched a decades-long campaign to press city, county, and state employers to eliminate discriminatory wage schedules for their employees.

In 1973, AFSCME Council 28 in Washington State partnered with then-Governor Daniel Evans to conduct a study of the state’s job classification system and pay scale. The results conclusively showed that jobs typically held by women were compensated at much lower rates than jobs typically held by men, even when the skill and education levels required were comparable. For instance, it was determined that Laundry Worker (typically female) and Toll Collector (typically male) were comparable based on the four factors described above, but Toll Collectors made about $200 more per month than Laundry Workers. Evans did not implement changes before leaving office in 1977. Subsequent governors also failed to do so. In 1981, Council 28 was bolstered by key events in the pay equity battle.

While the Equal Pay Act was somewhat limited, Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act provided an opportunity to challenge for broader protection because it prohibited employment discrimination on the basis of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin. A court case, originating in 1974 in Oregon (County of Washington, Oregon vs. Gunther) was brought by female prison guards alleging sex discrimination was the only reason their wages were lower than those of male prison guards. In 1981, the United States Supreme Court decided with Gunther that Title VII allowed for challenges based on the comparable worth theory and did not simply protect equal pay for equal work.

Also in 1981, employees of the city of San Jose, California, represented by AFSCME Local 101, went out on strike for eight days in July. They had held a sick-out in 1979 to force San Jose to conduct a wage comparison study. With results in hand, Local 101 tried to negotiate implementing fixes at the bargaining table, but it was going nowhere. Local 101 decided to strike, the first time such a strike had been conducted for the cause of pay equity. Local 101 was successful, and San Jose implemented a $1.4 million package to increase the compensation for female dominated jobs.

The Gunther decision and the success of Local 101’s strike reinvigorated Council 28’s efforts in Washington. In 1981, Council 28 filed a complaint with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC). This complaint did nothing to force Washington State to implement changes to its wage schedule, so in 1982, Council 28 filed a federal lawsuit against the state. AFSCME won at the district court level, but lost at the appeals court level. The union filed its own appeal, but ended up settling with Washington out of court in late 1985, over a decade after the initial study was conducted. The settlement awarded millions of dollars in back pay and raised salaries for typically female jobs.

AFSCME saw other pay equity successes both legislatively and at the bargaining table. In 1982, Minnesota became the first state to promote pay equity for public workers by statute. In 1991, police detention aides (mostly female) in New York won a lawsuit that originated in 1982 to bring their compensation in line with jail turnkeys (mostly male). And in 2001, custodians (mostly women) working for the Architects of the Capitol in Washington, DC won a wage increase to equal that of laborers (mostly men).

AFSCME saw numerous other victories over the years that can be explored at the Reuther Library. The AFSCME Program Development Department Records contain a great deal of material on a variety of women’s issues addressed by the union. The AFSCME Women's Rights Department Records contain consultant reports describing methodologies for conducting wage schedule surveys. The AFSCME Communications Department Records are valuable for researchers of this issue, especially the set of VHS oral history interviews with people involved in the Washington State campaign. AFSCME Office of the President: Jerry Wurf Records, AFSCME Office of the President: Gerald W. McEntee Records, and AFSCME Office of the Secretary-Treasurer: William Lucy Records also hold information that discusses this issue.

AFSCME was not the only organization engaged in pay equity promotion. Researchers should also view the SEIU District 925 Records, the SEIU District 925 Legacy Project, the Coalition of Labor Union Women Records, and the Susan Holleran Papers, among others.

Johanna Russ was the AFSCME Archivist from June 2008 to September 2013.

- jruss's blog

- Login to post comments

- Printer-friendly version

Reddit

Reddit Facebook

Facebook LinkedIn

LinkedIn